BLOG & PUBLICATIONS

Alongside undertaking research I also write about play, digital games and experimental research methods that combine art and design practices. I publish reports for industry, peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters and blog posts.

2024

IDEAS FROM EDO & THE FLOATING WORLD

September 2024Eleanor Dare, my friend and colleague, has been working on the development of the videogame. Right before she began work on it one of the issues we discussed was how to deal with two seemingly disparate desires for the game that arose from the children’s ideas, and those of the major adult stakeholders. For example, the Mersey Forest and the tree scientists had an educational agenda and values they wanted to pass on to children about how to interact with and care for trees, as well as very specific lessons they wanted to share about tree types and their growth. On the other hand, the children’s ideas were more fantastical having created mythical creatures and magical trees with golden acorns, and special powers as they aged. Yet, as I discussed previously, these child-designed narratives were rarely superficial but rather created to illustrate their awareness of politics and concerns about and ideas connected to the climate crisis.

I began thinking about ideas from when I had previously studied Japanese History and Japanese Art History. Specifically how Edo, the predecessor to Tokyo, had been controlled to such an extent that it necessitated the development of the Floating World (1615–1868). The two spaces lived in symbiosis with the Floating World acting as an escape for play and pleasure from the mundane and regimented life of Edo city. To me this reflects the differences between formal education and learning through free-play, as well as, the everyday structured school learning of the children we worked with, compared to the more chaotic workshops where children expressed their ideas and knowledge about trees through a range of analogue and digital making that was only loosely controlled.

Read more here.

CREATING CHARACTERS TO INHABIT TREESCAPES

March 2024

This is the second blog post about producing a videogame with children to allow them to play and tell stories about future landscapes with trees.

The work that I will be reflecting on here is part of the Digital Voices of the Future project led by Dr Simon Carr (University of Cumbria) where the project team (see full list of members below) are exploring how children can be involved in the co-design and production of a videogame about treescapes.

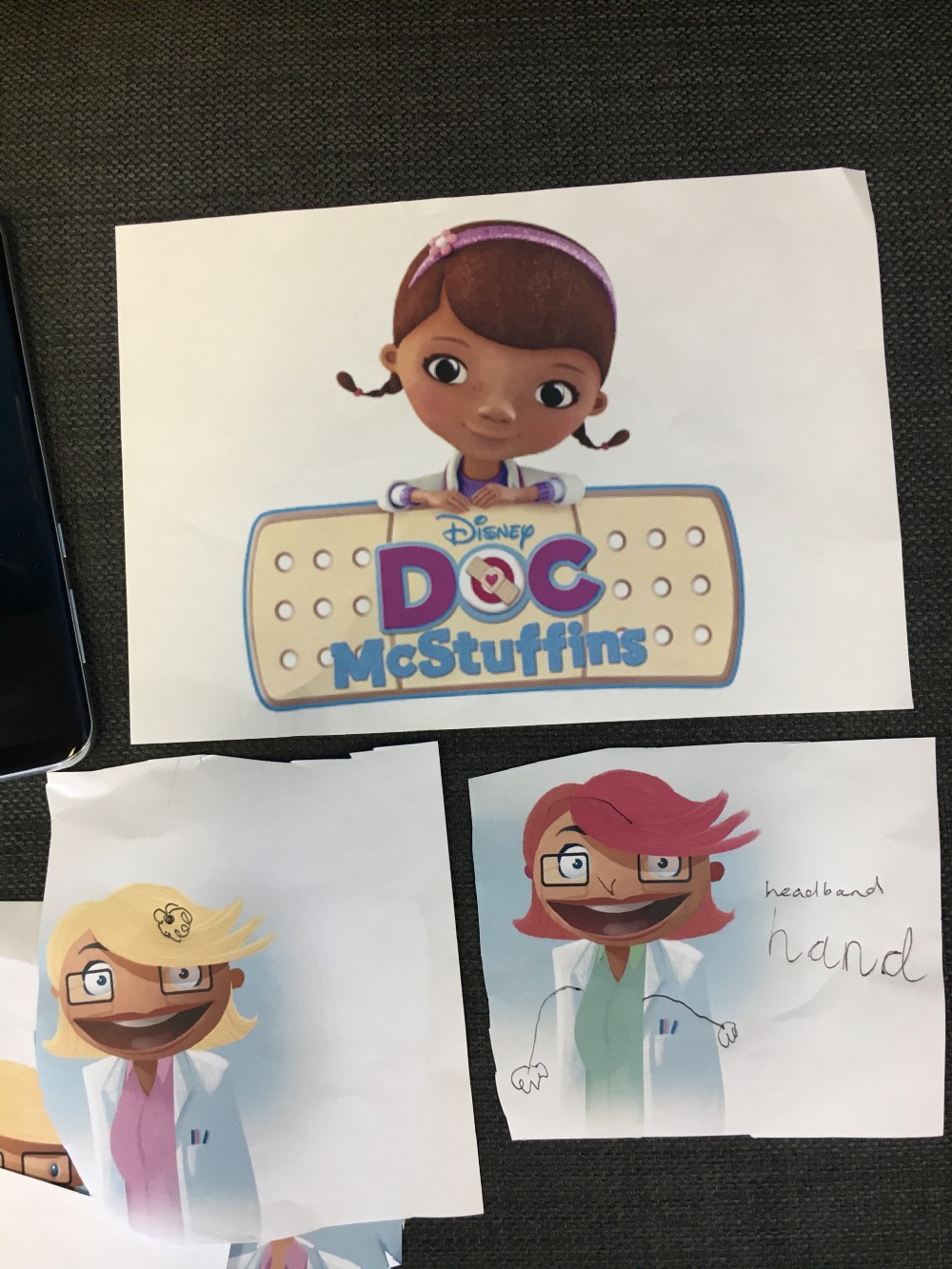

In order bring children into the design and production process, myself and Eleanor Dare devised workshops to be undertaken with late primary and early secondary school children to explore key elements involved in game development. Last time I wrote about my reflection on the worldbuilding workshops. This blog post is about the methods we created to bring children into the character design and gaming narratives processes and my reflections on those.

Read more here.

EXPLORING CHILDREN’S NOTIONS OF DIGITAL GOOD/BAD

Feburary 2024

This blog relates to an ESRC-funded project that is exploring children’s attitudes towards notions of digital good/bad. The team is made up of an interdisciplinary group of researchers that combines the arts and social sciences (Myself, John Potter, Angus Main, Eleanor Dare, Steve Love and Richard Nash). Within this disciplinary mix I call myself an Experience Design Researcher, which essentially means that I like to use art and design-based methods as part of the research process to work with children in a way that might be more engaging and meaningful for them than traditional ones such as interviews or surveys, and thus in turn the research workshops, I hope, are a kind of “experience”. Particularly I believe quite strongly that play is a form of communication in its own right, one of the strongest in childhood, and thus the methods I use are designed with this at the core.

Read more here.

CO-DESIGNING DIGITAL TREESCAPES WITH CHILDREN

Feburary 2024

Producing videogames with children to allow them to play and tell stories about future landscapes with trees.

This is the first blog that reports on my involvement in the Digital Voices of the Future project led by Dr Simon Carr at the University of Cumbria with Dr Ian Davenport and partners from the Manchester Metropolitan University (Dr Khawla Badwan & Dr Su Corcoran), Middlesex University (Prof Johan Siebers), the Mersey Forest (Dr Susannah Gill & Dr Dave Armson), and X||dinary Stories (myself and Dr Eleanor Dare).

Read more here.

PLAYFUL COMMUNICATION DESIGN IN THE CONTEXT OF CHILD HEALTH

January 2024

At the end of 2023 I took part in a knowledge exchange trip to Copenhagen as part of a project exploring how playful communication could be used for on and off-boarding child-patients in using the MRI playkit we developed previously. For example, how do we get children to take up the playkit, how does it fit into other aspects of their lives, what happens after they have used it and had the MRI scan? The intention was to explore this in three stages: (1) packaging design, (2) an international knowledge exchange trip to the play design team at Mary Elizabeth’s Hospital in Copenhagen, and (3) user testing with child-patients. This blog post reports on some ideas that arose for me during the Denmark trip.

Read more here.

2023

DEVELOPMENT AND INTRODUCTION OF A MIXED REALITIES PLAYKIT: DECREASING THE INCIDENCE OF GENERAL ANAESTHESIA FOR PAEDIATRIC MRI

November 2023Thompson, J., Yamada-Rice, D., Thompson, S., Murray, L. and Taylor, M. (2023) Development and introduction of a mixed realities playkit: decreasing the incidence of general anaesthesia for paediatric MRI. British Medical Journal, Early Innovation Report. Online first (09/11/23). doi:10.1136/ bmjinnov-2023-001083.

ADDRESSING THE ‘WHYS’ OF UK CHILDREN’S YOUTUBE USE: A PURPOSES APPROACH

October 2023Scott, F., Parry, B., Marsh, J., Lahmar, J., Nutbrown, B., Scholey, E., Baldi, P., Law, L., & Yamada-Rice, D. (2023) Addressing the ‘whys’ of UK children’s YouTube use: a purposes approach. Journal Social Media and Society.

Despite the widespread use of YouTube by children, there has been limited research undertaken on the “why” questions of their use. Past theoretical approaches have framed these questions in terms of broader individual needs and their relation to media use, though this work has mainly focused on adults and adolescents. This article presents relevant findings from a mixed methods study of children’s (aged 0–16) uses of social media in the United Kingdom to consider instead the “purposes” of children’s YouTube use, drawing on: (1) an online family survey; (2) family case studies; (3) child focus groups; and (4) child telephone interviews. “Purpose” is theorized in the article in relation to the ways children themselves make sense of and articulate the reasons they use YouTube or, in the case of parents and carers, for allowing, facilitating, or encouraging their children to use YouTube. Parents tended to frame the purposes of children’s YouTube use more instrumentally, focusing on perceived educational benefits and their own convenience needs. While sharing a focus on instrumental purposes, children sometimes emphasized broader dimensions of purpose, with an increased focus on humor, sensory, and hedonic dimensions. Children’s responses also emphasized the autotelic nature of play. The study foregrounded the extent to which the purposes of others (such as commercial entities) are served by children’s YouTube use. Seven child-centered, parent-centered, and “other” purposes for children’s YouTube use are discussed: cognitive, corporeal, cultural, collaborative, creative, commercial, and convenience.

THE FUTURE OF BROADCAST MEDIA ACCORDING TO KIDS: FINAL PROJECT REPORT

Yamada-Rice, D. & Dare, E. (2023) The Future of Broadcast Media According to Kids: Final Project Report. Available online.

GIPTON SPACE AGENCY

June 2023Using the Arts to Explore Tech Determinism

History shows us that it takes many different approaches to make change happen. The tactics that each group chooses are not a matter of personal taste but solutions to a particular problem. Too many years spent failing to make radical change happen can turn energies to smaller, achievable, single-issue campaigns. Conversely, the limits of reform push people and movements to revolt (Robinson, 2019, n.p).

This blog post reports on a workshop called “Gipton Space Agency” led by myself and Eleanor Dare (as part of our work for X||dinary Stories) that used art to critique tech determinism with a specific focus on space tourism. In a way turning energies to smaller, achievable, single-issue campaigns like others that have gone before.

Read more here

THE IMPORTANCE OF MULTIMODAL PLAY AND STORYTELLING TO A MIXED REALITIES PLAYKIT FOR PREPARING CHILDREN FOR AN MRI SCAN

MAY 2023Yamada-Rice, D. et al (2023) The Importance of Multimodal Play and Storytelling to a Mixed Realities Playkit for Preparing 4 to 10-year-olds for an MRI scan. Multimodality & Society, Volume 3, Issue 2.

This article examines the research and development of a mixed realities play-kit to prepare children for an MRI scan to be undertaken without the need for a General Anaesthetic. The kit uses three different types of play; augmented, virtual reality and physical to help children become familiar with the look of an MRI scanner, the noises it makes, the role of the radiographer, what to expect when they go to hospital and to practise staying still. We reflect on the initial multimodal research methods that were used to bring children into the first stages of the design and development process. These included, model making, drawing, play and informal conversations. From which, data were analysed with visual and thematic means to make an original contribution to the field of medtech design for children, in that we found young children (aged six and under) prefer to receive medical information through opportunities for multimodal play and storytelling. As a direct result of this finding, we matched different play types to the various areas of preparation outlined above. In doing so, paying attention to the specific affordances of the different ways in which modes are combined depending on if physical, augmented or virtual reality play are used. Such findings are likely to be useful to other researchers and developers creating medtech products for young children. For those interested in multimodality specifically, this article also provides insight into the connection between information, modes of communication and play and the application of these to research design.

CAN IMMERSIVE STORYTELLING WITH VR STAND UP TO THE EXPERIENCE OF VISITING ANTARCTICA

April 2023Lessons learnt from a unique setting and a fanatical audience that can guide immersive storytelling development more widely.

Working with the UK Antarctica Heritage Trust (UKAHT) I undertook research to look at their initial development of a Virtual Reality (VR) experience of Antarctica. On a personal level, I had never previously dreamed of visiting Antarctica, but as I came to learn through this project, it attracts a lot of fanatical people with a desire to do just that. These “fans” who became the research participants brought this project to life and highlighted insights that can be useful for those making immersive storytelling experiences more widely.

Read the full blog here.

KIDS INTEREST IN IMMERSIVE AND INTERACTIVE FUTURE BROADCASTING POSSIBILITIES

Feburary 2023This is the second of two posts about the future of broadcast media according to kids, and forms part of a project myself and Eleanor Dare have been undertaking through a commission by the University of York’s XR Stories. The first post focused on the methodology we created for children to show us directly how they think the dissemination of heritage brand story characters might be altered by emerging technologies. Here, I extend on the last post to highlight the methodology used to allow children to engage with world-building a heritage brand using emerging technologies, and their thoughts on immersive and interactive possibilities for future broadcasting.

Myself and Eleanor Dare have been commissioned by the University of York’s XR Stories to explore what kids want from broadcast media in the future. This is the first out of three blog posts that I will share on the project, and focuses on the methodology we created for children to show us directly how they think heritage-brand story characters might be altered by emerging technologies. The remaining two blog posts will focus on their ideas in relation to world building and kids thoughts on immersive and interactive future broadcasting prototypes.

The project is framed within the decline of children watching linear TV and the planned closure of traditional broadcasting of CBBC in 2025/6.

Read more here.

2022

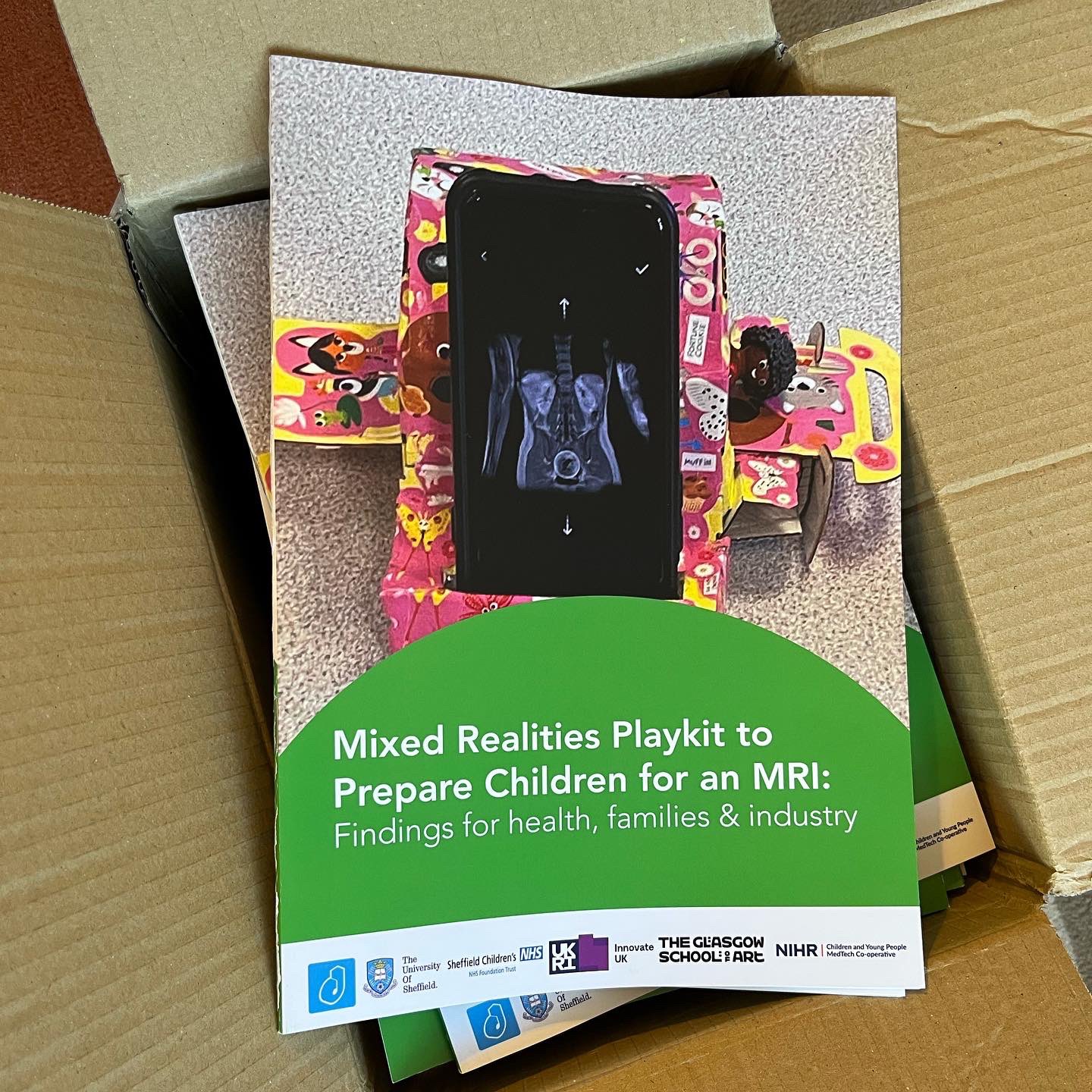

FINAL PROJECT REPORT

The final project report for the MRI playkit is available for download at the link below. It was given away, along with copies of the kit, at a dissemination event for health and kids media professionals held at the University of Sheffield, 13th October 2022.

![]()

Yamada-Rice, D., Thompson, J., Love, S., Thompson, S. & McQuillian,H. (2022) Mixed Realities Playkit to Prepare Children for an MRI Scan: Findings for health, families and industry. Available online at: <http://dubit.us/mri>.

![]()

Back when I was on the brink of leaving the Royal College of Art, I was part of a heated discussion on whether all information should be made to look beautiful. The discussion was in the context of my teaching on the MA in Information Experience Design, which was about turning data in o an experience for a particular audience. In order to explore the topic further, myself and colleagues; John Fass, Matt Lewis, Grace Pappas and Shelley James began to put together a special issue for Visual Communication journal entitled Information is Ugly. Today it was published: Vol. 20 (3) August 2022, ISSN 1470-3572.

![]()

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Main, A. & Yamada-Rice, D. (2022) Evading Big Brother: using visual methods to understand children’s perception of sensors and interest in subverting digital surveillance. Visual Communication, Vol. 20 (3).

If you are new to the processes of game design this book could serve as a useful introduction. The language is accessible and it is easy to dip in and out of the chapters, which broadly link to different parts of the design and development process. There are also a number of activities to try that might be helpful for someone starting out. However, my work sits across the games industry and academia and for a number of years I have been experimenting with ideas that offer additional perspectives that expand beyond those in this book. Thus, for the remainder of this review I critique Lemarchand’s work in relation to my own in the hope that others will experiment too.

To begin with I was struck by the masculine tone of some of the terminology in the book: ‘blue sky thinking’, ‘a metastructure of the creative process: how to manage our time and plan our projects’ (p. 1). In recent work with Eleanor Dare (Dare & Yamada-Rice, 2022), we asked the audience to question the extent to which the terminology and structures of gaming software build on those from capitalism (Keogh and Nicoll, 2019) and suggested alternative systems drawn from magic (e.g., Kuhn, 2019) and queering (e.g. Ahmed, 2006) could be used to disrupt these. Considering how alternative systems can be used within game design is not only acting responsibly to the creative process, but is also a form of ‘design justice’ (Costanza-Chock, 2020) that widens the audience being designed for/with. This also questions Lemarchand’s narrow frameing of gaming audiences, which does not match the wide range of people that play games. Such language also reflects the gender imbalance in the industry so should be questioned from this perspective too.

As universities become more closely intertwined with industry; creating curricula that feeds their future needs, giving honoury degrees or taking sponsorship for infrastructure etc it becomes ever more important for students to be told that it is OK to see their studies as a platform for experimentation. I encourage students to explore each stage of the design and production process as widely as possible. For example, on page 13 Lemarchand advocates for mind mapping as a way in which ‘blue sky thinking’ can occur and the game design process can begin. Later he mentions storyboarding, ‘Wikipedia: random, or your favourite divination technique’ (p.15). In my research and practice I situate my earliest ideas around the narrative/story/information at the heart of the gaming experience, and then draw on notions of multimodal social semiotics (Kress, 2010) to explore how the gaming narrative is altered by the modes and ultimately the platforms included in the game design. A focus on multimodality links well with Lemarchand ideas that:

Game designers are communicators. The games that we make communicate ideas and feelings to our audience of players. Games are highly conceptual, built of logic, number, space, and language. These are conveyed in image, sound, touch, and the other modalities of our senses. (p. 43)

However, Lemarchand continues to states that the key to ‘effective communication is clarity, brevity, and active listening’ (p.45). Given the focus on modes and senses I believe that effective communication through games is more complicated and involves deep exploration of the match between mode and materials, and how these are used by the communicator and received by the player. Much of this relates to Gibson’s idea of affordances, which in turn connects to the player experience. In chapter 7, Lemarchand also talks about experience as a goal of good game design and likewise introduces Gibson’s theory of affordance (p.105). However, it also needs to be remembered that with XR gaming technologies traditional affordances need not be applied because VR makes it possible to mess with scale and immersion etc.

Chapter 3 is focused on research, but the methods offered are more search than research. I believe research is fundamental to good design and production processes and should extend across all stages. Thus, research could have been discussed within each of the chapters to illustrate this. In any case a deeper discussion of research would allow readers to understand how it can have a direct or indirect correlation with the gaming narrative and mechanics. For example, when working on a train themed app for my employer Dubit, I observed children playing with physical train toys to understand movements, sounds and narratives within their play. These were then carried over to the digital design process. However, research methods can also be less directly connected, and in doing so bring about innovation in the design process. As part of MA-level teaching I ask students to consider their gaming narrative from a modal perspective. In doing so, they are introduced to specialists such as the work of Kate McLean on smell mapping (Perkins & McLean, 2020) or McCloud (1993) on visual narratives structures. There are opportunities also to draw on social sciences or to bring gaming practices into the research process. For further discussion on this see here. Isolating one mode at a time and researching in this way can lead to discovering new perspectives and ideas.

Lemarchand also seems to draw a distinction between research and making but the two need not be separate processes. Ingold (2013) also shows how making is part of the thinking process which he illustrates by demonstrating the long human history of knowledge production in this way. Having said this, Lemarchand is an advocate for prototyping which can be seen when he writes:

“ If the game engine you would like to use is not yet available to you, just find a game engine that you can use today and start building immediately.” (p.31)

I agree, using readily accessible gaming platforms such as Roblox can make it possible to begin thinking, design, building immediately and act as an initial means of prototyping.

Overall, game design should be a complex process because as I have shown elsewhere (Yamada-Rice, 2021) it needs to consider the game, that is it’s modes, platforms, materials and associated affordances, the player and the places in which it will be played. One of the simplest ways to do this, which Lemarchand does not mention, is to play as widely as possible to become familiar with games and play in the broadest sense.

References

Ahmed, A. (2006). Queer Phenomenology: Orientation, objects and others, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need (Information Policy), Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

Dare, E. & Yamada-Rice, D. (2022) Virtual magic: sleight of hand in immersive storytelling. Keynote presentation for: Connected Screens Playing with Immersive Systems. Leeds Beckett University, 30th March 2022

Ingold, T. (2013) Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

Keogh, B., Nicoll, B. (2019). The Unity Game Engine and the Circuits of Cultural Software, Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. Kindle Edition.

Kress, G. (2010) Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London and New York: Routledge.

Kuhn, G. (2019) Experiencing the Impossible: The Science of Magic. The MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

McCloud, S. (1993) Understand Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Collins.

Perkins, C., & McLean, K. (2020). Smell walking and mapping. In S. M. Hall, & H. Holmes (Eds.), Mundane methods: Innovative ways to research the everyday (p. 156-173). Manchester University Press.

Yamada-Rice, D. (2021) Is now the perfect timing for a break through in connected play? Medium. Available online at: <https://komesanyamada.medium.com/is-now-the-perfect-timing-for-connected-play-4a44363c9147> [Accessed 11/04/22]

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Dare, E. & Yamada-Rice, D. (2022) Reading the Cards: Critical Chatbots, Tarot and Drawing as an Epistemological Repositioning to Defend Against the Neoliberal Structures of Art Education. In: Filimowicz, M. (ed) Systematic Bias: Algorithms and Society. London: Routledge

HOW DO YOU MAKE SENSE OF DIVERSITY WHEN ALL AROUND YOU IS PREJUDICE?

JAN 2022

Just 22% of UK children and young people in Dubit’s recent research believe authority figures such as the Government treats everyone fairly, with figures rising only slightly with regards to the Police (30%) and teachers (36%). Additionally, the data seems to mirror contemporary discussion around white privilege and how this is entrenched in power structures including education. In relation to these key findings, this blog post seeks to ask the reader to think about how children and young people make sense of diversity when all around them is prejudice.

This is the third in a series of posts that discusses the findings of a study undertaken to discover young people’s views on their lives and the world. To recap, more than 500 twelve to fifteen-year-olds from across the UK shared views in a two-stage methodology that included 32 one-to-one interviews with young people in London, Bournemouth, Gateshead and Newcastle, and an additional 514 survey responses from across the UK. The aim was to understand what young people care and worry about and where they gain knowledge that informs their opinions.

Read more hereThe final project report for the MRI playkit is available for download at the link below. It was given away, along with copies of the kit, at a dissemination event for health and kids media professionals held at the University of Sheffield, 13th October 2022.

Yamada-Rice, D., Thompson, J., Love, S., Thompson, S. & McQuillian,H. (2022) Mixed Realities Playkit to Prepare Children for an MRI Scan: Findings for health, families and industry. Available online at: <http://dubit.us/mri>.

INFORMATION IS UGLY

July 2022Back when I was on the brink of leaving the Royal College of Art, I was part of a heated discussion on whether all information should be made to look beautiful. The discussion was in the context of my teaching on the MA in Information Experience Design, which was about turning data in o an experience for a particular audience. In order to explore the topic further, myself and colleagues; John Fass, Matt Lewis, Grace Pappas and Shelley James began to put together a special issue for Visual Communication journal entitled Information is Ugly. Today it was published: Vol. 20 (3) August 2022, ISSN 1470-3572.

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Main, A. & Yamada-Rice, D. (2022) Evading Big Brother: using visual methods to understand children’s perception of sensors and interest in subverting digital surveillance. Visual Communication, Vol. 20 (3).

A REVIEW: LEMARCHAND, R. (2021) A PLAYFUL PRODUCTION PROCESS: FOR GAME DESIGNNERS (AND EVERYONE): MASSACHUSETTS: MIT PRESS.

If you are new to the processes of game design this book could serve as a useful introduction. The language is accessible and it is easy to dip in and out of the chapters, which broadly link to different parts of the design and development process. There are also a number of activities to try that might be helpful for someone starting out. However, my work sits across the games industry and academia and for a number of years I have been experimenting with ideas that offer additional perspectives that expand beyond those in this book. Thus, for the remainder of this review I critique Lemarchand’s work in relation to my own in the hope that others will experiment too.

To begin with I was struck by the masculine tone of some of the terminology in the book: ‘blue sky thinking’, ‘a metastructure of the creative process: how to manage our time and plan our projects’ (p. 1). In recent work with Eleanor Dare (Dare & Yamada-Rice, 2022), we asked the audience to question the extent to which the terminology and structures of gaming software build on those from capitalism (Keogh and Nicoll, 2019) and suggested alternative systems drawn from magic (e.g., Kuhn, 2019) and queering (e.g. Ahmed, 2006) could be used to disrupt these. Considering how alternative systems can be used within game design is not only acting responsibly to the creative process, but is also a form of ‘design justice’ (Costanza-Chock, 2020) that widens the audience being designed for/with. This also questions Lemarchand’s narrow frameing of gaming audiences, which does not match the wide range of people that play games. Such language also reflects the gender imbalance in the industry so should be questioned from this perspective too.

As universities become more closely intertwined with industry; creating curricula that feeds their future needs, giving honoury degrees or taking sponsorship for infrastructure etc it becomes ever more important for students to be told that it is OK to see their studies as a platform for experimentation. I encourage students to explore each stage of the design and production process as widely as possible. For example, on page 13 Lemarchand advocates for mind mapping as a way in which ‘blue sky thinking’ can occur and the game design process can begin. Later he mentions storyboarding, ‘Wikipedia: random, or your favourite divination technique’ (p.15). In my research and practice I situate my earliest ideas around the narrative/story/information at the heart of the gaming experience, and then draw on notions of multimodal social semiotics (Kress, 2010) to explore how the gaming narrative is altered by the modes and ultimately the platforms included in the game design. A focus on multimodality links well with Lemarchand ideas that:

Game designers are communicators. The games that we make communicate ideas and feelings to our audience of players. Games are highly conceptual, built of logic, number, space, and language. These are conveyed in image, sound, touch, and the other modalities of our senses. (p. 43)

However, Lemarchand continues to states that the key to ‘effective communication is clarity, brevity, and active listening’ (p.45). Given the focus on modes and senses I believe that effective communication through games is more complicated and involves deep exploration of the match between mode and materials, and how these are used by the communicator and received by the player. Much of this relates to Gibson’s idea of affordances, which in turn connects to the player experience. In chapter 7, Lemarchand also talks about experience as a goal of good game design and likewise introduces Gibson’s theory of affordance (p.105). However, it also needs to be remembered that with XR gaming technologies traditional affordances need not be applied because VR makes it possible to mess with scale and immersion etc.

Chapter 3 is focused on research, but the methods offered are more search than research. I believe research is fundamental to good design and production processes and should extend across all stages. Thus, research could have been discussed within each of the chapters to illustrate this. In any case a deeper discussion of research would allow readers to understand how it can have a direct or indirect correlation with the gaming narrative and mechanics. For example, when working on a train themed app for my employer Dubit, I observed children playing with physical train toys to understand movements, sounds and narratives within their play. These were then carried over to the digital design process. However, research methods can also be less directly connected, and in doing so bring about innovation in the design process. As part of MA-level teaching I ask students to consider their gaming narrative from a modal perspective. In doing so, they are introduced to specialists such as the work of Kate McLean on smell mapping (Perkins & McLean, 2020) or McCloud (1993) on visual narratives structures. There are opportunities also to draw on social sciences or to bring gaming practices into the research process. For further discussion on this see here. Isolating one mode at a time and researching in this way can lead to discovering new perspectives and ideas.

Lemarchand also seems to draw a distinction between research and making but the two need not be separate processes. Ingold (2013) also shows how making is part of the thinking process which he illustrates by demonstrating the long human history of knowledge production in this way. Having said this, Lemarchand is an advocate for prototyping which can be seen when he writes:

“ If the game engine you would like to use is not yet available to you, just find a game engine that you can use today and start building immediately.” (p.31)

I agree, using readily accessible gaming platforms such as Roblox can make it possible to begin thinking, design, building immediately and act as an initial means of prototyping.

Overall, game design should be a complex process because as I have shown elsewhere (Yamada-Rice, 2021) it needs to consider the game, that is it’s modes, platforms, materials and associated affordances, the player and the places in which it will be played. One of the simplest ways to do this, which Lemarchand does not mention, is to play as widely as possible to become familiar with games and play in the broadest sense.

References

Ahmed, A. (2006). Queer Phenomenology: Orientation, objects and others, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need (Information Policy), Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

Dare, E. & Yamada-Rice, D. (2022) Virtual magic: sleight of hand in immersive storytelling. Keynote presentation for: Connected Screens Playing with Immersive Systems. Leeds Beckett University, 30th March 2022

Ingold, T. (2013) Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

Keogh, B., Nicoll, B. (2019). The Unity Game Engine and the Circuits of Cultural Software, Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. Kindle Edition.

Kress, G. (2010) Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London and New York: Routledge.

Kuhn, G. (2019) Experiencing the Impossible: The Science of Magic. The MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

McCloud, S. (1993) Understand Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Collins.

Perkins, C., & McLean, K. (2020). Smell walking and mapping. In S. M. Hall, & H. Holmes (Eds.), Mundane methods: Innovative ways to research the everyday (p. 156-173). Manchester University Press.

Yamada-Rice, D. (2021) Is now the perfect timing for a break through in connected play? Medium. Available online at: <https://komesanyamada.medium.com/is-now-the-perfect-timing-for-connected-play-4a44363c9147> [Accessed 11/04/22]

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Dare, E. & Yamada-Rice, D. (2022) Reading the Cards: Critical Chatbots, Tarot and Drawing as an Epistemological Repositioning to Defend Against the Neoliberal Structures of Art Education. In: Filimowicz, M. (ed) Systematic Bias: Algorithms and Society. London: Routledge

HOW DO YOU MAKE SENSE OF DIVERSITY WHEN ALL AROUND YOU IS PREJUDICE?

JAN 2022Just 22% of UK children and young people in Dubit’s recent research believe authority figures such as the Government treats everyone fairly, with figures rising only slightly with regards to the Police (30%) and teachers (36%). Additionally, the data seems to mirror contemporary discussion around white privilege and how this is entrenched in power structures including education. In relation to these key findings, this blog post seeks to ask the reader to think about how children and young people make sense of diversity when all around them is prejudice.

This is the third in a series of posts that discusses the findings of a study undertaken to discover young people’s views on their lives and the world. To recap, more than 500 twelve to fifteen-year-olds from across the UK shared views in a two-stage methodology that included 32 one-to-one interviews with young people in London, Bournemouth, Gateshead and Newcastle, and an additional 514 survey responses from across the UK. The aim was to understand what young people care and worry about and where they gain knowledge that informs their opinions.

2021

STATE OF THE NATION

DEC 2021Education, Algorithms & Opportunities for Kids Media to Create Third Spaces for Learning

Recently, Dubit and the Children’s Media Foundation undertook research to discover young people’s views on their lives and the world- a youth “State of the Nation”.

More than 500 twelve to fifteen-year-olds from across the UK shared views in a two-stage methodology that included 32 one-to-one interviews with young people in London, Bournemouth, Gateshead and Newcastle, and an additional 514 survey responses from across the UK.

Overarching topics included climate change, diversity, schooling, social media, friends, money, and more. The aim was to understand what young people care and worry about and where they gain knowledge that informs their opinions.

This post focused on education is the first in a series of posts covering key aspects of the findings.

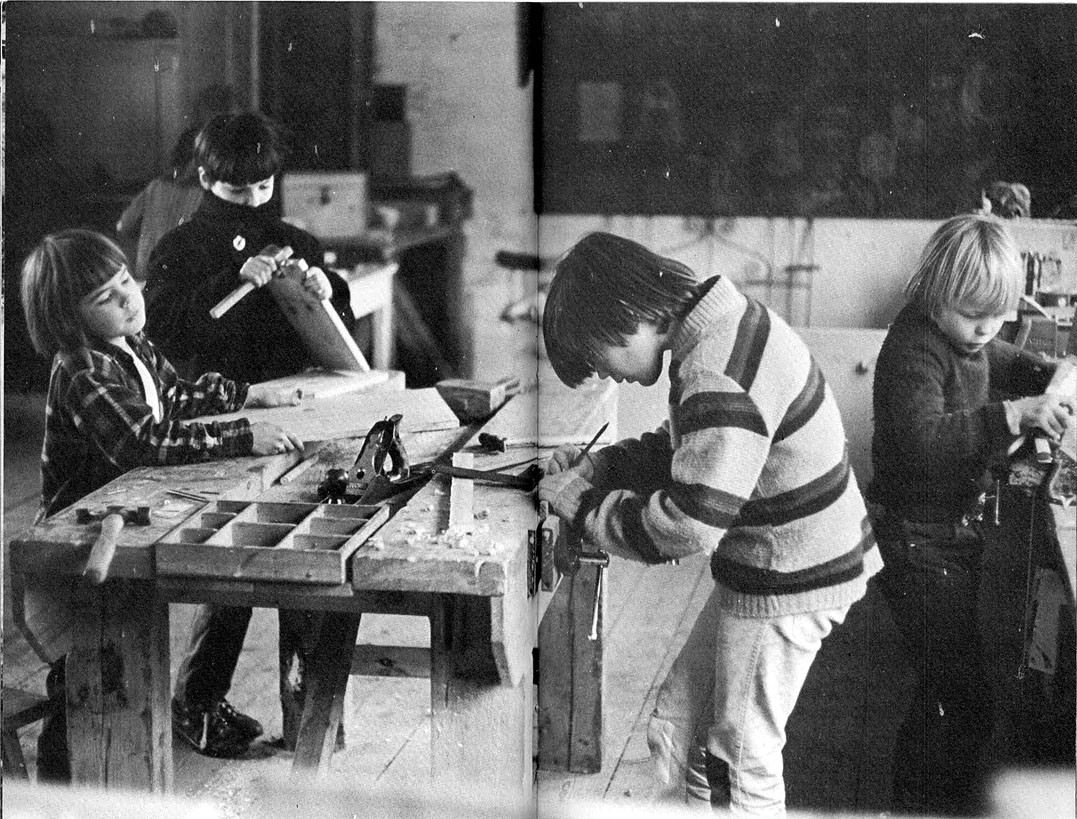

How best to educate children and young people has been much debated throughout history and is closely related to historic, social and cultural values. In 1762, the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau caused a stir by writing a proposal for how to educate an imaginary child called Emile into adulthood by letting him learn purely from nature and everyday life experiences. Since then, the argument for unstructured education, or learning for learning’s sake, has reoccured in notable examples and movements. A S Neill opened the famed Summerhill in 1922 which was described as a ‘do-as-you-please-school’ where formal lessons were optional (Saffange, 1994).

CHILD-CENTERED DESIGN FOR HEALTH

NOV 2021Play and storytelling are important aspects of children’s learning about serious issues in health and medicine.

Typically, design for child health is made by adults and the resulting designs are top heavy on the serious nature of medical information. Obviously, tech for health must foreground medical accuracy, but my work on designing play to improve health outcomes shows that adult designers are missing two crucial aspects that might make a big difference to children’s uptake and interaction with medical products- play and storytelling.

Understanding the importance to children of play and storytelling in medical contexts came about through a two-year Innovate UK-funded research and development project. We included children in creating a mixed realities play kit to help reduce the need for a General Anaesthetic (GA) among children undergoing a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan. Details of the outcome of the project can be found here, but the intention of this article is to show how making the project child-centred brought about new insight into what children want from technologies for health.

RESEARCHING THE METAVERSE

SEPT 2021The Metaverse is coming, and it’s far more than a buzzword for kids and teens. If you’re not yet familiar with the term, metaverse refers to global, always-on virtual spaces that are “omni-experiential” (i.e., places to consume and create, with gaming, entertainment, learning, work, communication and socialising in a single, connected immersive environment.

At the start of 2021, Kidscreen predicted that companies would quickly begin making themselves “metaverse-ready”:

This year, brands will start to create metaverse studios — teams focused on integrating their IPs into multiple digital worlds, including implementing multi-game engagement strategies. Non-gaming companies will build experiences that can be played across platforms. Games will continue to serve as sandbox tools, which kids will use, repurpose and play with their own rules–not necessarily how they were originally designed. (Kidscreen)

Seeing this same trend, Dubit is pioneering the way in undertaking qualitative research on kids engagement with current proto-metaverses (e.g., Roblox, Core and Crayta) to supplement the wealth of quantitive data they already have. For example, Dubit Trends found that:

- Over half of US 8–12 year olds said they had played Roblox in the last week;

- In the UK, Roblox and Minecraft tied for the game that the most 8–12 year olds had played within the last week;

- In the US, Roblox was the 4th most-played game among 8–12 year olds in the past week;

- Around a third of US and UK kids said they had played Roblox in previous 24 hours, suggesting that Roblox is a daily habit for many young people.

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Nash, R., Yamada-Rice, D., Dare, E., Love, S., Main, A., Potter, D., Rodrigues, D. (2021) Using a collaborative zine to co-produce knowledge about location-based virtual reality experiences. Qualitative Research Journal, Vol.21 (2).

Image by Richard Nash

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Ikon, E., Wee, C., Dare, E., Lewis, M., Biderman, K., Gordon, L., Pochodzaj, J., and Yamada-Rice, D, 'Exercises in Exorcism, Ways of Healing

(through) Art Education'. In: Baier, W., Canepa, E., Golemis, H. (eds) (2021) Capitalism's

Deadly Threat: transform! London: Merlin Press.

NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US

JUNE 2021

What does it mean to be inclusive when working with kids in research?

‘Nothing About Us Without Us’ is the title of a chapter in Costanza-Chock’s (2020) book ‘Design Justice’. The chapter starts by outlining the controversy that followed a Google employee sharing a memo called ‘echo chamber’ that suggested the company, like most tech companies, had limited diversity and thus the products being designed within them were not inclusive. In the children’s tech and digital play industry, there is a similar lack of diversity in the workers developing products for younger audiences. Bringing a more diverse workforce onboard is one aspect that needs addressing; making sure we are connected to diverse groups of children and families is another part of the equation. They are connected. Working with diverse groups of children during the research and development phases of design means children from under represented groups are much more likely to see a place for themselves in our industry as they grow up.

What does it mean to be inclusive when working with kids in research?

‘Nothing About Us Without Us’ is the title of a chapter in Costanza-Chock’s (2020) book ‘Design Justice’. The chapter starts by outlining the controversy that followed a Google employee sharing a memo called ‘echo chamber’ that suggested the company, like most tech companies, had limited diversity and thus the products being designed within them were not inclusive. In the children’s tech and digital play industry, there is a similar lack of diversity in the workers developing products for younger audiences. Bringing a more diverse workforce onboard is one aspect that needs addressing; making sure we are connected to diverse groups of children and families is another part of the equation. They are connected. Working with diverse groups of children during the research and development phases of design means children from under represented groups are much more likely to see a place for themselves in our industry as they grow up.

Image: Kinetic Landscape by Susan Atwill, Nirav Beni, JP Guerrier, Ance Janevica, Lera Kelemen, Shangyun Wu

Yamada-Rice, D. (2021) Children’s interactive storytelling in Virtual Reality, Multimodality & Society, Vol. 1 (1), p.48-67.

THE DATA EXPERIENCE MACHINE

MARCH 2021Turning surveys into experiences to provide engaging means for children to share their opinions

The UN Rights of the Child (1989) stipulates that children must be given a voice in issues that affect them. Throughout my research and design work for/with children I have always sought to find better ways to include their voices and ideas. I have written a lot about using art and design-based methods for including children in qualitative research, but what about in quantitive research?

In my role as a Senior Tutor in Information Experience Design at the Royal College of Art, MA students are taught how to bring research together with art and design practices, to create experiences for a wide range of audiences. This got me thinking about how a good audience experience should not only be the end point of research during dissemination, but could also be incorporated into finding engaging and interactive methods for data collection. This seems to be particularly relevant to traditional quantitive research with children who are unlikely to engage with a questionnaire in a meaningful way.

Image: Tunin’ by Yaprak Goker, Lucy Anderson, Evan Reinhound and Noura Andrea Nassar

IS NOW THE PERFECT TIMING FOR A BREAKTHROUGH IN CONNECTED PLAY?

MARCH 2021

In my work in both academia and the play industry I spend a lot of time exploring what makes a good play experience. From considering the best methods for observing and understanding play to how it can be theorised to make new or better play experiences. The COVID-19 pandemic has altered play, in such a way, that it might be time to reconsider how designers and manufacturers of play products can best respond to these evolving needs.

I’ll start by showing why making an excellent connected-play experience is so difficult, before illustrating why it might be worth the while at this particular moment in time.

The Complexities of Designing a Connected Play Experience

It is possible to position play as a balance between three connected elements, that when combined impact on player experience:

- The product (toy/software)

- Players

- Places (contexts of play)

As toys, devices and software advance the ways of positioning play in relation to the above three elements multiplies; keeping a good design balance between them becomes harder to maintain. Here’s why:

Play Product

At the level of the product, decisions must be made by the designer in relation to the affordances of the toy or other play product- essentially what it is possible to do with it. For a physical toy, this is limited to materials and size etc. This means that when the player creates a narrative with the physical toy during play, the choice of what sounds or movements to make in enacting the story are decisions made by the child.

Image Credit

Image CreditINTERVIEW WITH ME BY THE RCA

Meet the RCA: Dr Dylan Yamada-Rice Dylan Yamada-Rice is Senior Tutor for our MA Information Experience Design (IED) and an artist/researcher whose work pushes at the intersection between experimental design and the social sciences. Her multi-disciplinary background in academia and her boundary pushing work in industry complement her teaching for a programme which is all about finding new ways of presenting information using a combination of digital and physical which increase user engagement, often collapsing binary notions of the human and the digital.

We talked about her interdisciplinary background, how she moves between academia and industry and where she thinks the future of digital storytelling lies.

Your PhD was on children’s understanding of the visual mode in Japanese environments, what led you to this subject?

I became really interested in Japan after my first degree at SOAS where I studied Art, Archaeology and Geography which involved quite a lot of Japanese art history. After graduation I undertook postgraduate research in Japanese Art History at Kyoto University, and when that ended I decided to stay on to teach English to children.

As a teacher, I started to realise that the whole way of making sense of the world in Japanese was different to English. In English, we learn through sounds that represent meaning, whereas Japanese is largely pictorial – you're making sense of the world through your eyes rather than your ears.

This interest in children’s learning prompted me to study for Master’s degrees in social sciences first in Early Childhood Education and then Research Methods. My PhD – which involved working with a group of kids in Japan for a year and trying to understand how they comprehended the world around them through images – brought together all these different threads that I thought were quite separate parts of me; my love of drawing and Japanese semiotics, and also an interest in children, which I always felt like I’d better not admit to because somehow children were seen as lesser.

ESRC & AHRC funded UK Japan Location-Based VR Network Research

ESRC & AHRC funded UK Japan Location-Based VR Network ResearchDoes your multi-disciplinary background inform your approach to teaching as Acting Head of IED?

Definitely. MA Information Experience Design is all about finding innovative new ways to present data in ways that make users want to engage with it. That’s why we take people from a wide range of backgrounds. So we’ll have someone from architecture, someone from philosophy and a fine artist working on the same brief. Staff backgrounds are just as wide-ranging. We encourage students to capitalise on these diverse disciplines to present data in ways that resonate with people.

A good example is of a student I had once who was looking at collected data in bell graphs. In the end, they cast them as actual bells and played them. So you’re taking something that is usually on a page and turning it into something physical that can be interacted with – you’re engaging with data in a new way.

In my work, this is where drawing comes in. Kids don’t do A, B, C – they’re tangential. To get to what you want to know, you have to do something more physical like making or drawing to engage them. When you have the data you have to decide how to make it interesting and accessible with a mix of analogue and digital mediums.

VR & Mixed-Realities Play Kit to prepare Under 10s for an MRI

VR & Mixed-Realities Play Kit to prepare Under 10s for an MRIAs well as being Acting Head of MA IED, you also work part-time for digital games company Dubit. Can you tell us about your work there?

I’m Senior Research Manager at Dubit. My role there has allowed me to link up the two worlds of industry and academia to do a different type of research and produce a different kind of product. In academia you research an idea in depth that isn’t attached to an end product, while at Dubit, I can look at what children actually do with an app.

You’re currently working with Dubit to produce a Virtual Reality (VR) ‘Play Kit’ to prepare children for MRI scans. Can you tell us about it?

Yes, the project is funded by Innovate UK and is in partnership with Dubit. We’re using Dubit’s data on kid’s entertainment and applying it to a health setting. MRI machines are stressful experiences for children – they’re very noisy and require children to stay still for a long time. So, we’re producing an app and a physical play kit that will help alleviate these stresses and prepare children for their scan. We were about to take it to test in hospitals when Covid-19 hit, so now we’re seeking new ways to do the research at a distance.

What do you feel VR can contribute the experience of play and/or storytelling? Is this kind of technology going to be the future of storytelling?

I think the future of storytelling is mixed realities. VR on it’s own is not as exciting as VR on a really well designed set or if you have elements of Augmented Reality (AR) that reveal something in the actual world. If you asked kids about Pokémon Go, they might say that adults made an app that revealed Pokémon that were always there in the actual world. The future of storytelling is how you do that for adults as well as for kids.

Graphic narrative drawn as part of the analysis phase of the UK-Japan Location-based VR Network., Dylan Yamada-Rice

2020

FINAL PROJECT REPORT

Yamada-Rice, D., Dare, E. Main, A., Potter, J., Ando, A. Miyoshi, K., Narumi, T., Beshani, S., Clark, A., Duszenko, I. Love, S., Nash, R., Rodrigues, D., Stearman, N. (2020) Location-Based Virtual Reality Experiences for Children: Japan-UK Knowledge Exchange Network: Final Project Report. Available online at <URL>.

2019

Yamada-Rice, D., Rodrigues, D. & Zubrycka, J. (2019) Makerspaces and Virtual Reality Chapter 5. In: Blum-Ross, A., Kumpulainen, K. & Marsh, J. (eds) Enhancing Digital Literacy and Creativity: Makerspaces in the Early Years. Routledge.

JOURNAL ARTICLE

Yamada-Rice, D. & Love, S., (2019) Designing tech for health: Developing a mixed reality play kit to help children who need and MRI scan, RIAS Quarterly, Vol.38, p 57.

CULTURE, HISTORY & VR DEVELOPMENT

JULY 2019

What has culture and history got to do with VR development? Here I discuss some initial ideas on the topic…

Kress (2003) describes how communication practices arise from changes in technology, social and cultural practices. Geertz (1973) defines culture as: ‘the fabric of meaning in terms of which human beings interpret their experience and guide their actions [while] social structure is the form that action takes, the actually existing network of social relations’ (p. 145). In other words, our very specific cultural and personal backgrounds control our interpretation of experiences. In relation to my own experiences of Japanese location-based VR content this is in relation to both being British, but also having spent my twenties and early thirties living in Japan. As a result my interpretation of several of the Japanese experiences drew directly from this connection to the culture; one as partial insider but also an outsider. For example, on a visit to Hashilus I played with one of their VR experiences called Happy Oshare (Fashionable) Time.

MODES, MATERIALS & PERFORMANCE IN THE DESIGN OF LOCATION-BASED VR

JULY 2019

How do modes, materials and performance affect the design of a virtual reality experience? Here I review some location-based VR experiences from Japan in relation to these three areas to offer some insight for future development.

The VR Park Shibuya is an arcade hosting location-based VR experiences. These are site specific content designed for VR play away from the home setting. As a result, location-based VR experiences often have a physical component which provides a different experience to that which can be achieved on a home console such as the Play Station VR. This is something more akin to fit in with the ‘experience economy’ and thus in the best case scenarios the physical set can bring an extra dimension to the VR play worthy of making an audience feel they are paying for an “experience” they could not have elsewhere.

The VR Park occupies one floor of a well established game centre. Each floor is dedicated to different types of gaming content. The ground floor for example has mostly prize based games like the UFO catcher.

MEDIA MEDICINE

JULY 2019

“How can media help children and their families to stay healthy? From understanding how their bodies work, coping with illness, learning about health and fitness, or improving their medical experiences; worthy doesn’t have to be boring and a dose of media medicine can be just what doctor ordered.” (The Children’s Media Conference)Last week at the Children’s Media Conference, I was lucky enough to present on a panel about using kid’s media to help child health.

I was there to talk about Dubit’s Innovate UK -funded project, with the Royal College of Art, Glasgow School of Art, Sheffield Children’s Hospital NHS Trust and the University of Sheffield, to build a playkit for preparing children to have an MRI scan. As part of the playkit contains a VR component I also drew on ideas from an AHRC/ESRC-funded network which has explored location-based VR experiences for children. I was accompanied by a range of very knowledgeable people working in this field and this got me thinking about what my tips for design in this area would be.

BOOK CHAPTER

Yamada-Rice, D. (2019) Including Children in the Design of the Internet of Toys: In Mascheroni, G. & Holloway, D. (Eds) The Internet of Toys: Practices, Affordances and the Political Economy of Children’s Smart play.

EXHAUSTED PIRATES & INSOMNIAC ASTRONAUTS

NOV 2019

Using design-based workshops to understand children’s sleep knowledge

This blog post reflects on sleep workshops that myself and Amy Clark undertook on behalf of Dubit in order to inform a new play about sleep called Sweet Dreams by tutti frutti, a theatre company specialising in productions for young children. The development of the play is funded by the Wellcome Trust and includes Sheffield Children Hospital NHS Trust and the Children’s Sleep Charity as partners. These two partners are experts in child sleep, and along with a wide body of research, can testify that sleep deprivation has a serious impact on emotional, physical and mental health, and is a growing problem for children and their families.

Thus, Tutti frutti decided to respond to this need for wider knowledge about the importance of sleep by embedding information on its benefits and the fears children may have of it, into the Sweet Dreams play they are producing for 3–7 year olds.

KIDS DESIGNING TECH FOR HEALTH

APRIL 2019

How much information would young children like to prepare for an MRI scan?

How can design and play-based methods help children feed their ideas into the design of a med-tech product?

Recently, myself, another researcher from Dubit and academic partners spent time in primary schools working with children aged 4–10 years old. The aim was to gain their ideas for a med-tech product in the form of a play kit to help children their age have an MRI scan.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive scanning method that employs strong magnetic fields and radio waves to examine parts of the body. An MRI scan is used to facilitate diagnosis, help determine treatment and evaluate its effectiveness. In 2016–17, 142,020 MRI scans were carried out in England on children aged 0–14 (Dixon, 2017). Dixon (2017) also notes that MRI activity is expanding rapidly with an increase of 10% between 2015–16 and 2016–17.

HUMAN & NON-HUMAN ENTITIES IN JAPANESE STORIES

JULY 2019

In Japan there is an affinity with non-human entities. Of course this includes other living creatures and nature but it also extends to machines and an otherworldly-ness of spirits and gods that according to Shintoism reside in many things. In the Barbican AI exhibition ‘More than Human’, a whole section is dedicated to Shintoism and the connection between human and non-human things in Japan. This is used as a framework for thinking about the connection between people and machines in an era of rapid AI development.

“In the Japanese religion of Shinto, Kami are Devine forces or spirits of nature that surpass human intelligence. There are more than 8 million kami that live in natural forms including the sun, oceans, mountains, trees, rocks and animals. They are also believed to live in tools, technologies and extraordinary people. According to Shinto beliefs, all these entities respect each other and live in harmony.”

“In Japanese culture and art, life breathes in people, living creatures and artificial objects alike. This perspective is reflected in animation, games and technology.” Wall writing from More than Human, Barbican

JAN 2019

A year ago Dubit co-produced and hosted one of the roadshow events organised by Alison Norrington of StoryCentral for the Children’s Media Foundation

on the topic of children and Virtual Reality. Our involvement in this work provides an example of how research, design and development can marry up well.

The Research

The event at Dubit focused on bringing together industry experts and academics on the topic of ‘crossing physical and virtual worlds in children’s VR’.

The event started with an introduction to an Arts and Humanities Research Council funded project on design standards for location-based immersive experiences by Professor Steve Love of Glasgow School of Art. Following this, I shared insights into Dubit’s ‘Children and VR’ study with a particular emphasis on the data and findings that showed how children wanted easier ways to acclimatise from physical to virtual world. Dubit also shared it’ s perspectives on telling narratives across physical and virtual domains.

The final two presentations came from Eleanor Dare of Royal College of Art about her AR books and Professor Mark Mon Williams of the University of Leeds who talked how design could help alleviate some of the pressure VR places on some children’s eyes.

Read more here

RESEARCH FOR THE DESIGN OF DIGITAL PLAY

APRIL 2019 Image: Dubit

Image: DubitInsight into research processes behind the development of digital products.

Twice a week I work for the children’s media agency Dubit in the area of research leading to design. Dubit is one of only a few agencies that combine research and development under one roof. This is unfortunate because the connection between research and digital development is a vital part of producing a good design. Here I outline four types of research that are user-led and help ensure the products developed match the audience they are designed for.

Trends Data looks at the broadest picture, using a quantitative process to reap a broad insight into children’s lives. Dubit collects data in this manner using a 6-monthly online survey of children aged 2–15 years and their parents, which is conducted across 8 countries. The survey asks questions related to children’s tech and media use so we can understand which types of content are engaging children and what technology they have access to.

Understanding these international trends allows us to know where the products we produce tie in with what else children are using and the extent to which we are competing with similar content.

Read more here

![]() Image: Deborah Rodrigues

Image: Deborah Rodrigues

Myself and others have been awarded ESRC/AHRC funding to build a Japan- UK knowledge exchange network focused on location-based Virtual Reality (VR) experiences for children, which has a growing demand in a range of sectors that include entertainment, education and health. It builds on emerging research findings that suggest that context specific VR is evolving as the next generation of immersive experiences and thus has raised questions around how best to create an experience that crosses physical and virtual spaces.BUILDING A JAPAN-UK NETWORK TO FOCUS ON LOCATION-BASED VR EXPERIENCES

MARCH 2019

Image: Deborah Rodrigues

Image: Deborah RodriguesThe network will use some of the existing ways in which location-based VR experiences are emerging as a starting point to identify what further research and development needs to be undertaken in this area. These include:

Projecting the VR narrative into the physical environment, i.e. Marshmallow Laser Feast’s Ocean of Air

DEVELOPING A DIGITAL PLAY KIT TO HELP CHILDREN UNDERTAKEN AN MRI

JAN 2019Do you ever wonder what it feels like to have an MRI scan?

Perhaps you have already had an MRI and are familiar with the need to remain very still for up to an hour or more, as well as how noisy the scanners are. These are two reasons that 58% of MRIs on 5–10 year olds are performed under General Aesthetic. Figures for children younger than 5 years are harder to calculate. However, in the UK around 60,000 MRI exams are carried out on 4–10 year old’s annually.

UK-based research firm and digital studio Dubit has been awarded prestigious Innovate UK funding to expand into the area of gaming for child health by developing a digital play kit to prepare children for undergoing an MRI.

2018

CAN MAKING HEADSETS TEACH CHILDREN HOW VR WORKS?

JAN 2018

For three years, Dubit has been engaged in research around children and virtual reality. Beyond basic questions of health and safety, engagement and enjoyment, UI and UX, it’s critical with this emerging medium to ask how children can learn to critique VR content. As with any medium, we should want young people across cultures to be critically literate — choosing and engaging thoughtfully across diverse VR content, but also to be content creators themselves.

Making builds an active connection between thinking and knowing. Anthropologist Tim Ingold (2013)* wrote that humans have forever learned about the world through our hands.

While VR content creation is still a complex process, perhaps enabling young people to design their own VR headsets, with an eye toward enhancing the immersive experience, would spark critical thinking about how VR works. I tested this idea in my role as a Senior Tutor at London’s Royal College of Art, with postgraduate students, building from key findings in Dubit’s Children and Virtual Reality study.

Read more here

PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLE

Yamada-Rice, D. (2018) Licking planets and

Stomping on Buildings: children’s interactions with curated spaces in Virtual

Reality. Children's

Geographies,

Vol.16, No. 5. MULTIMODALITY & INFORMATION EXPERIENCE DESIGN

Information Experience Design (IED) work is multimodal. This workshop showed participants how an understanding of multimodal theory can be used to expand their IED practice. There was a focus on:

- The meaning of a mode

- What it means to transduct information from one mode to another

- The ways in which modes relate to culture and history

- Information that is lost and gained when one mode is used over another

The workshop started with an outline of multimodal theory similar to the last session (see here).

In the last multimodality workshop students were asked to observe one mode across the ground floor of the RCA White City campus and find a way to represent it, i.e. to see how the building smells and find a way of representing it. Having done this with groups of social science students in the past I was surprised when none of the IED students choose to represent the mode they were representing in writing.

Much of the literature on multimodal analysis within the social sciences uses a form of transcription that breaks down the multimodal whole by transcribing each mode into words and placing them in a table (such as the example below by Mavers, 2005).

PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLE

Yamada-Rice, D. (2018) 'Designing Play: young children’s play and communication practices in relation to designers’ intentions for their toy' Global Studies of Childhood 8 (1). pp. 5–22.

ONLINE PUBLICATION

Yamada-Rice, D. and Marsh, J., (2018) Using Augmented and virtual Reality in the Early Childhood Curriculum. Printed Publication available online.

DO EMERGING FORMS OF DIGITAL PLAY REQUIRE NEW MEANS FOR ANALYSING DATA?

JAN 2018 Image: Dylan Yamada-Rice

Image: Dylan Yamada-RiceIt’s fascinating and fun to observe a child at play. Even more fascinating, though, is the underlying engagement and learning that can be uncovered through emerging means of transcribing and analyzing data.

Increasingly, research with children in an industry context uses big data from online surveys or harvests data directly from the technology young people are using. Working as a Senior Research Manager at Dubit and a Senior Tutor in Information Experience Design at the Royal College of Art, I too collect and analyse data around children’s play, to guide the design of new digital products.

Still, I remain an advocate of the smaller-scale qualitative insights gained from visual and experimental methods. While more resource intensive, observing and talking to children about their use of digital content can provide very rich accounts of what engages them, that may be obscured in quantitative data alone.

Currently, myself and others at Dubit are studying children’s use of Virtual Reality (VR), primarily via detailed observation. Does VR affect children’s balance? How do children move in a virtual environment? We video-record their play to answer these questions, but I had to invent new means for transcribing and analyzing that data to delve deeper into the reasons behind children’s actions.

Read more here

![]()

PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLE

Marsh, J. A., Plowman, L., Bishop, J, Lahmar, J and Scott, F, Yamada-Rice, D. (2018), Play and creativity in young children’s use of apps. British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 49, No.4.

NOV 2018

Marsh, J. A., Plowman, L., Bishop, J, Lahmar, J and Scott, F, Yamada-Rice, D. (2018), Play and creativity in young children’s use of apps. British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 49, No.4.

EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH METHODS TEACHING: SENSORY ETHNOGRAPHY

NOV 2018

Photo: Daisy Buckle

It then went on to introduce two academics that have shown how the study of seemingly everyday things can be used to provide a deep understanding of the world around us. These were Sarah Pink’s work on Sensory Ethnography and Tim Ingold’s study of lines.

The brief for the workshop was to build a den that could keep out the cold. To do this groups were asked to divide into Den Builders and Sensory Ethnographers. The role of the Sensory Ethnographers was to find a means of recording the experience of Den Building by focussing on one particular mode. This idea was developed from the work of IED student Daisy Buckle who is exploring how building human sized nests might help with people’s mental and emotional well-being.

MAKING AS A WAY OF UNDERSTANDING HOW NARRATIVE FOR VR WORKS

MAY 2018

In what are still “early days” for Virtual Reality (VR), experiences predominately are being developed in the following areas:

· Health and medicine

· Entertainment and Gaming

· Education

· Art/ cultural sector

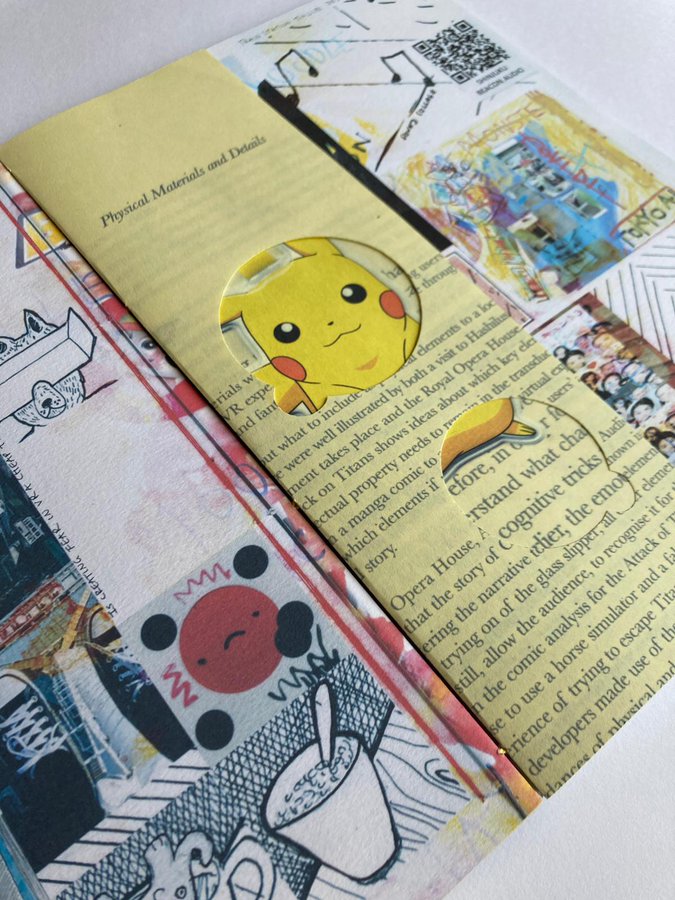

Narrative design is important to all these areas, resulting in wide discussion of how narrative should be developed for VR’s unique attributes. Increasingly, companies with a tradition of immersive storytelling in non-digital forms are leading innovation in VR storytelling. The Royal Opera House, for example, created Audience Labs to combine historic stories with cutting edge technologies.

I’ve been exploring what makes good narrative in VR since beginning as lead researcher on Dubit’s Children and Virtual Reality project. I’ve also led a paper prototyping workshop on the subject with a group of MA Information Experience Design (IED) students at the Royal College of Art.

![]()

This workshop started by considering how an ethnographic approach can be used to collect first-hand data that can in turn to be used to inform Information Experience Design work.

It then went on to introduce two academics that have shown how the study of seemingly everyday things can be used to provide a deep understanding of the world around us. These were Sarah Pink’s work on Sensory Ethnography and Tim Ingold’s study of lines.

The brief for the workshop was to build a den that could keep out the cold. To do this groups were asked to divide into Den Builders and Sensory Ethnographers. The role of the Sensory Ethnographers was to find a means of recording the experience of Den Building by focussing on one particular mode. This idea was developed from the work of IED student Daisy Buckle who is exploring how building human sized nests might help with people’s mental and emotional well-being.

MAKING AS A WAY OF UNDERSTANDING HOW NARRATIVE FOR VR WORKS

MAY 2018In what are still “early days” for Virtual Reality (VR), experiences predominately are being developed in the following areas:

· Health and medicine

· Entertainment and Gaming

· Education

· Art/ cultural sector

Narrative design is important to all these areas, resulting in wide discussion of how narrative should be developed for VR’s unique attributes. Increasingly, companies with a tradition of immersive storytelling in non-digital forms are leading innovation in VR storytelling. The Royal Opera House, for example, created Audience Labs to combine historic stories with cutting edge technologies.

I’ve been exploring what makes good narrative in VR since beginning as lead researcher on Dubit’s Children and Virtual Reality project. I’ve also led a paper prototyping workshop on the subject with a group of MA Information Experience Design (IED) students at the Royal College of Art.

2017

Yamada-Rice, D. (2017) Designing Play for Dark Times. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, Vol.18 (2). p. 196-212.

PROJECT REPORT

Yamada-Rice, D., Mushtaq, F., Woodgate, A., Bosmans, D, Douthwaite, A, Douthwaite, I, Harris, W, Holt, R, Kleeman, D, Marsh, J, Milovidov, E, Mon Williams, M, Parry, B, Riddler, A, Robinson, P, Rodrigues, D, Thompson, S and Whitley, S, (2017), Children and Virtual Reality: Emerging Possibilities and Challenges. Available online at http://childrenvr.org.

Yamada-Rice, D. (2017) "Designing Play for Dark Times' Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 18 (2). pp. 196–212

PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLE

Yamada-Rice, D. (2017) 'Using visual and digital research methods with young children'. In: Christensen, P. & James, A. (eds) Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices. Routledge

EU REPORT

Yamada-Rice, D. (2017) Designing connected play: Perspectives from combining industry and academic know-how. In: Chaudron S., Di Gioia R., Gemo M., Holloway D., Marsh J., Mascheroni G., Peter J., Yamada-Rice D. Kaleidoscope on the Internet of Toys - Safety, security, privacy and societal insights, EUR 28397 EN, doi:10.2788/05383

2016

BOOK CHAPTER

Marsh, J. and Yamada-Rice, D. (2016) Bringing Pudsey to Life: Young Children’s Use of Augmented Reality Apps. In: Kucirkova, N. and Falloon, G. (eds) Apps, Technology and Younger Learners. Routledge

PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLE

Marsh, J., Plowman, L., Yamada-Rice, D., Bishop, J. & Scott, F.(2016) Digital play: a new classification Early Years an International Research Journal, Vol, 36 (3). p. 242-253.

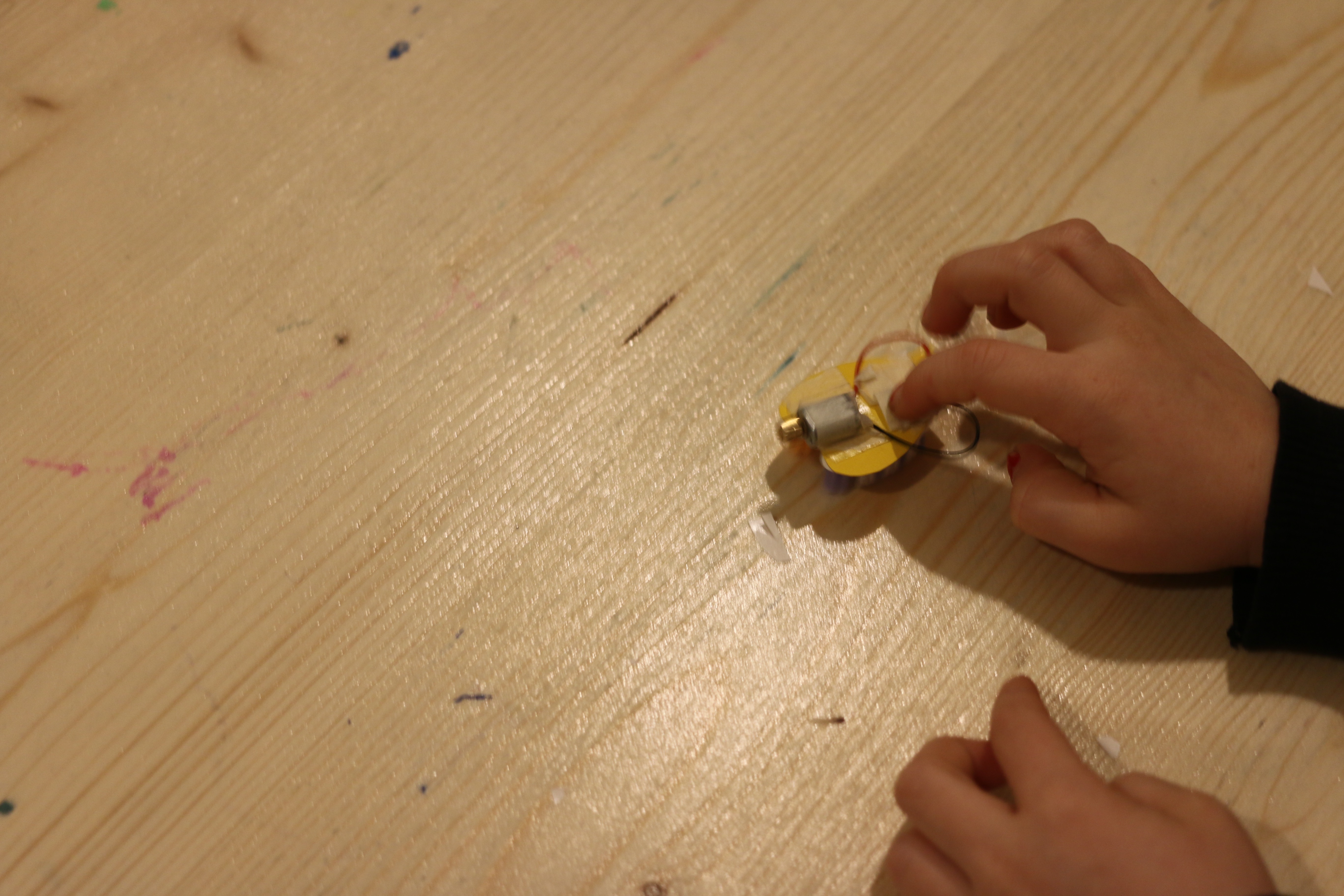

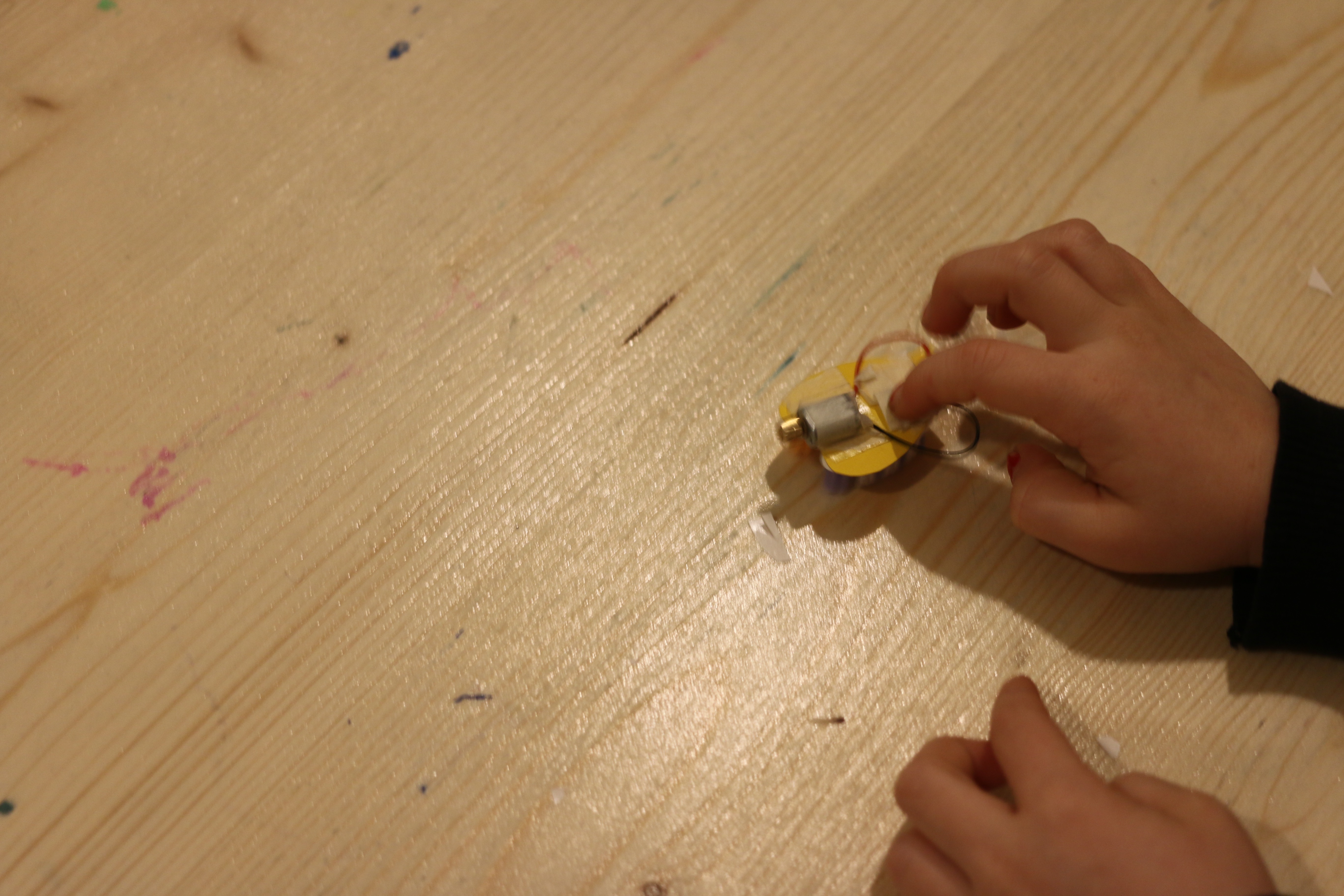

I attended a Glück workshop run by Deborah Rodrigues that taught young children how to make their own miniature robots from toothbrush heads. The workshop took place at Der Malfisch, which is a cafe, play and art space for young children.

The design for the toothbrush robots was relatively simple but still fiddly. Deborah explained the process by projecting a video of the process onto the art space wall. The children needed to fix a red wire from a motor to the top of the toothbrush heads, place a battery on top and then add a black wire on top of that. This made the motor vibrate and move the toothbrush robot. The wires were held in place by tape that made them very sensitive. Part of the process was for children to understand how the circuit was made and thus be able to repair their own robots.

This was the first prototype for the Ava Kai dolls. The main starting point was their belief in open-ended play. The Vai Kai founders saw this as the starting point. So they started with this childhood ideal rather than the product or the technology. With this in mind they designed a toy that could be fully customised by each child using a selection of different shaped wooden pegs.

The founders felt that the technology should complement traditional play. They allowed the toy to be opened up so that things could be stored inside.

One of the cofounders, Justyne Zubrycke mentioned how she was influenced by Machiko Kasahara ideas on 'Device Art'.

"More recently, interactive art has redefined forms of art and the role of artists. What we call device art is a form of media art that integrates art and technology as well as design, entertainment, and popular culture. Instead of regarding technology as a mere tool serving the art, as it is commonly seen, we propose a model in which technology is at the core of artworks." (Kasahara)

As it happens I have been interested in Japanese art history for a long time and the ideas described by Kasahara can, I believe, can be traced throughout Japanese art history, that is the ideal that art should also blend seamlessly with everyday life so that it is used not only looked at.

In play sessions with children Vai Kai noticed some differences in the way in which children of different ages played with the prototype. 3-5-year-olds really enjoyed adding the pegs and spent a long time doing this, but this did not hold the attention of older children so well. They experimented with adding in technology, such as using an ipad to hunt for the prototype, but the children seemed only to look at the screen. In the end it was decided that the Ava Kai prototype was too open-ended.

Read more hereMarsh, J. and Yamada-Rice, D. (2016) Bringing Pudsey to Life: Young Children’s Use of Augmented Reality Apps. In: Kucirkova, N. and Falloon, G. (eds) Apps, Technology and Younger Learners. Routledge

PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLE

Marsh, J., Plowman, L., Yamada-Rice, D., Bishop, J. & Scott, F.(2016) Digital play: a new classification Early Years an International Research Journal, Vol, 36 (3). p. 242-253.

TOOTHBRUSH ROBOT

JAN 2016I attended a Glück workshop run by Deborah Rodrigues that taught young children how to make their own miniature robots from toothbrush heads. The workshop took place at Der Malfisch, which is a cafe, play and art space for young children.

The design for the toothbrush robots was relatively simple but still fiddly. Deborah explained the process by projecting a video of the process onto the art space wall. The children needed to fix a red wire from a motor to the top of the toothbrush heads, place a battery on top and then add a black wire on top of that. This made the motor vibrate and move the toothbrush robot. The wires were held in place by tape that made them very sensitive. Part of the process was for children to understand how the circuit was made and thus be able to repair their own robots.

THE EVOLUTION OF AVAKAI

FEB 2016This was the first prototype for the Ava Kai dolls. The main starting point was their belief in open-ended play. The Vai Kai founders saw this as the starting point. So they started with this childhood ideal rather than the product or the technology. With this in mind they designed a toy that could be fully customised by each child using a selection of different shaped wooden pegs.

The founders felt that the technology should complement traditional play. They allowed the toy to be opened up so that things could be stored inside.

One of the cofounders, Justyne Zubrycke mentioned how she was influenced by Machiko Kasahara ideas on 'Device Art'.

"More recently, interactive art has redefined forms of art and the role of artists. What we call device art is a form of media art that integrates art and technology as well as design, entertainment, and popular culture. Instead of regarding technology as a mere tool serving the art, as it is commonly seen, we propose a model in which technology is at the core of artworks." (Kasahara)

As it happens I have been interested in Japanese art history for a long time and the ideas described by Kasahara can, I believe, can be traced throughout Japanese art history, that is the ideal that art should also blend seamlessly with everyday life so that it is used not only looked at.

In play sessions with children Vai Kai noticed some differences in the way in which children of different ages played with the prototype. 3-5-year-olds really enjoyed adding the pegs and spent a long time doing this, but this did not hold the attention of older children so well. They experimented with adding in technology, such as using an ipad to hunt for the prototype, but the children seemed only to look at the screen. In the end it was decided that the Ava Kai prototype was too open-ended.

UNBOXING THE AVAKAI COMPARTMENT

APRIL 2016From the start [of the project lookng at designers intentions for their smart-toy called Avakai] I was interested in the small compartment in the Avakai's base. I thought it would be of interest to young children who I knew from personal experiences liked to collect "stuff" in containers. Here are a couple of examples of collections from my young child: