UK-Japan Location-Based VR Network

January 2019- May 2020

Jointly funded by ESRC & AHRC

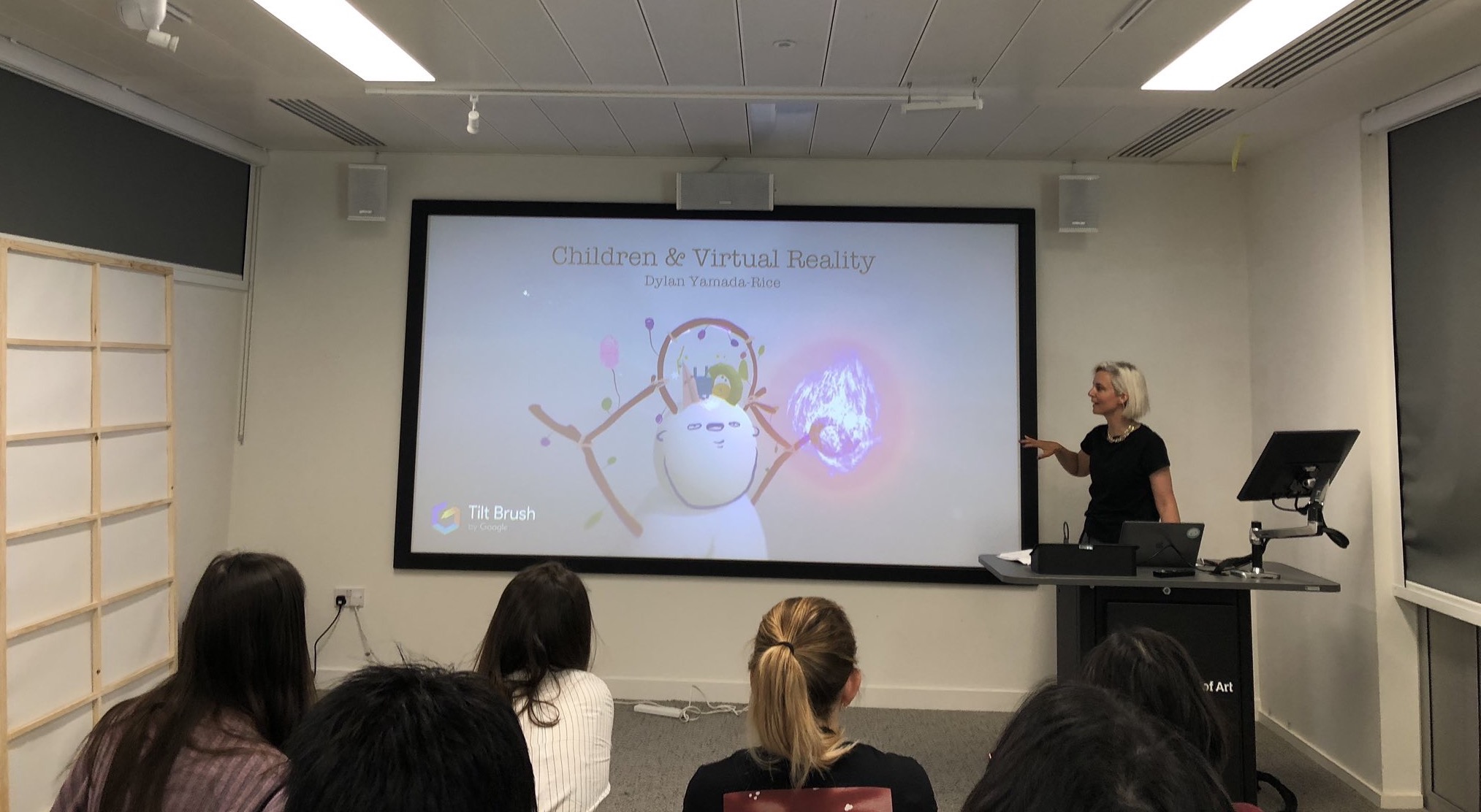

Dylan Yamada-Rice (PI), Co-Is: John Potter, University College London, Angus Main & Eleanor Dare, Royal College of Art, Steve Love, Glasgow School of Art, Takuji Narumi, University of Tokyo and partners Andrew Douthwaite, WEARVR, Kei Miyoshi, Location-based VR Association Japan and Akihiro Ando, Hashilus

The overall intention of this knowledge exchange (KE) project was to bring together a network of academics and digital gaming industry partners in Japan and the UK to join up knowledge, begin researching the current state of VR experiences and technologies, and to understand the best methodologies for including children in the design of VR experiences for them. This was undertaken so that this knowledge can be applied to areas in which VR is evolving for children, such as entertainment, education and health care. Further details are available on the project blog

Key findings from the project related to (1) The Virtual Unreal, (2) Illusion and Magic (3)Physical Materials and Details and (4) Emotions and Social Experiences. Further details of these are available in the publication listed below.

Further Project Details

There is a demand for location-based VR experiences for children in a range of sectors that include entertainment, education and health. The need is evidenced in the findings of the commercially-funded research entitled ‘Children and VR (CVR)’ that shows how 8 to 12-year-olds use VR in highly tactile ways, that cross virtual and physical environments. This is the case even when the content has not been designed with this intention and thus indicates a desire for mixed reality as opposed to purely digital immersive experiences (Yamada-Rice, et al, 2017).

The need for further research on location-based experiences is also apparent in other sectors too such as education, wider creative industries (i.e. theatre and museums), as well as child health.

John Potter (Co-I) has been studying VR and children as part of the ‘Playing the Archive’ project (EPSRC funded). In the health sector, Dylan Yamada-Rice has received Innovate UK funding to produce a mixed reality play kit to help children have an MRI scan without general aesthetic. Additionally, Steve Love (Co-I) is concluding an AHRC/EPSRC Research and Partnership Development call for the Next Generation of Immersive Experiences which is focused on setting design standards for VR for child use.

The chance to undertake KE activities with Japanese partners is further important because research on semiotics and related social practices shows how unlike English, Japanese communication practices foregrounds emotional expression rather than objects and time (e.g. Shelton & Okayama, 2006). This is particularly relevant to VR because the medium is increasingly considered a good match for content that centres on emotions and empathy which are important to both game, entertainment and health design, and is emerging as the key affordance that is separating this medium from others that have gone before.

Human and Non-human Entities in Japanese Stories

In Japan there is an affinity with non-human entities. Of course this includes other living creatures and nature but it also extends to machines and an otherworldly-ness of spirits and gods that according to Shintoism reside in many things. In the Barbican AI exhibition ‘More than Human’, a whole section is dedicated to Shintoism and the connection between human and non-human things in Japan. This is used as a framework for thinking about the connection between people and machines in an era of rapid AI development.

“In the Japanese religion of Shinto, Kami are Devine forces or spirits of nature that surpass human intelligence. There are more than 8 million kami that live in natural forms including the sun, oceans, mountains, trees, rocks and animals. They are also believed to live in tools, technologies and extraordinary people. According to Shinto beliefs, all these entities respect each other and live in harmony.”

“In Japanese culture and art, life breathes in people, living creatures and artificial objects alike. This perspective is reflected in animation, games and technology.”

Wall writing from More than Human, Barbican

The exhibition continued from this starting point, to draw on objects from popular culture and show how such ideas have been integrated into other aspects of Japanese life. For example, the Manga and Anime series entitled Doremon, which is the name given to a robot-cat that travels back from the 22nd Century to help a boy. The exhibition states that Doremon has ‘had tremendous influence on Japanese robotic philosophy and technological developments’.

“In fiction, characters can be humans, animals, machines or artificial objects with human emotions. From early childhood, most Japanese people are accustomed to stories where non-human entities co exist with people. This has greatly influenced Japanese attitudes towards technology” (More than Human, the Barbican).

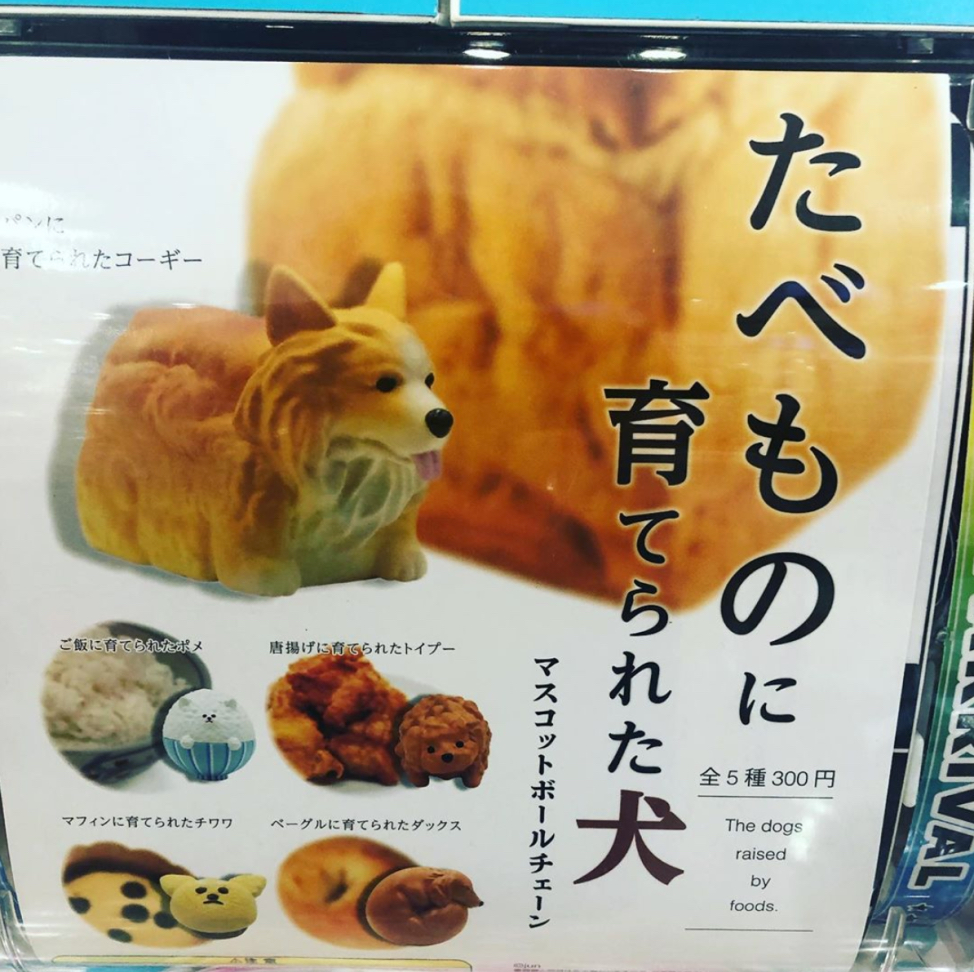

On a visit to the Kyoto International Manga Museum during the network field trip, an exhibition highlighted how stories from manga cross into other platforms such as toys:

The final paragraph of the above description shows how in a similar way to Manga, toys are reflections of wider social, cultural and historic practices. Theo Van Leeuwen, in relation to his work on semiotic and multimodal practices, has also shown how Western toys such as Lego are also a reflection of wider social patterns.

For the past few years, I have been an avid collector of gachagacha (also known as gachapon). These are plastic capsules delivered from a vending machine. Each capsule forms a lucky dip of one small toy from a series. I have been documenting these on an Instagram account and tagging themes. These themes show many are a combination of a living and non-living entity such as animal combined with food:

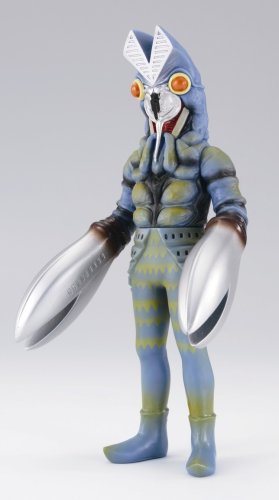

Above is an image of the fish fight sequence of the Robot Show and on the left a Kaiju monster toy from the TV show Ultraman. Perhaps these are both a reflection of the wider connection between Japan and the Ocean:

What does all this mean for understanding site-specific VR experiences? For me, it questions whether in an era in which VR, XR and AI are emerging together, perhaps there are other cultural histories that can allow us to theorise the connection between human and non-human entities including machines and robots to think about how we design for these evolving technologies.

Culture, History and VR Development

Kress (2003) describes how communication practices arise from changes in technology, social and cultural practices. Geertz (1973) defines culture as: ‘the fabric of meaning in terms of which human beings interpret their experience and guide their actions [while] social structure is the form that action takes, the actually existing network of social relations’ (p. 145). In other words, our very specific cultural and personal backgrounds control our interpretation of experiences. In relation to my own experiences of Japanese location-based VR content this is in relation to both being British, but also having spent my twenties and early thirties living in Japan. As a result my interpretation of several of the Japanese experiences drew directly from this connection to the culture; one as partial insider but also an outsider. For example, on a visit to Hashilus I played with one of their VR experiences called Happy Oshare (Fashionable) Time.

Happy Oshare Time

In this game players take on an avatar in the common manga aesthetic of big eyes, big hair and cute clothing. In the first part of the experience players have the opportunity to choose their hair styles and eye colour, to try out different outfits and accessories. The experience is multiplayer and so you are able to comment on your friends choices and enjoy the dressing up activity together- a social and performative experience.

In the second part of the experience, players compete to sing and dance at a concert by catching stars in time with the music. I attached this experience to a range of other historic and culturally specific practices. Long before smartphones were widespread and taking selfies had appeared on the scene there was Purikura.

Purikura

The word purikura is a condensed version of printo kurabu, the Japanese rendering of the English words ‘Print Club’. It refers to the Japanese practice of individuals taking selfies usually with friends, in specially designed booths, which provide a range of backgrounds and also the means for adding writing, drawing and assorted emoji and stamps to the photograph. Once completed the photographs are printed quickly as a sheet of stickers to be cut and shared. In the past they were collected in albums or stuck to personal belongings. With the advent of smartphones Purikura also began to be forwarded to mobile phones for dissemination.

Researchers of Purikuri practices have tended to focus on how it has been taken up by girls and young women in Japan and as a result tend to focus on how their form and creation reflect gender (Chalfen and Murai 2001; Miller 2003; Okabe et al 2006; 2009). However, at the level of the text itself it can be analysed as being part of a wider cultural practice. Just as I am doing in the analysis of this particular VR experience.

The performative aspect of the VR experience reminded me of other cultural practices such as Karaoke, Maid Cafes and Cos Play.

Karoke has been adapted into the English language and so does not need any explanation. The term Cosplay comes from combining and shortening two words ‘Costume’ and ‘Play’, and refers to the practice of dressing up and performing as a specific character usually from Manga or Anime. Off the top of my head such spaces for playing and imagining go back at least as far as the Edo Period (1603-1868) where society was so tightly controlled that on the outskirts of old Tokyo a pleasure district existed called the Floating World. This offered a space away from the rules of the everyday and allowed the chance to play and make believe.

The Floating World: ‘was a realm of the imagination that fostered a kind of aesthetic which cherished the passing moment the temporal flux for their own sake.’

Guth, 1996, p.29

Indeed, dressing up was also a part of this world. In the rule stricken Edo many types of clothing were banned but in the floating world fashion became elaborate. Drawings of the floating world known as Ukiyoe depicted these clothes and when the woodblock prints reached those within Edo also influenced a desire to wear these types of flamboyant fabrics and styles.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861): Princess Takiyasha Calling Up a Monstrous Skeleton Spectre at the Haunted Old Palace at Soma (1844-1848).

In recent years, it could be argued that maid cafes take on this role of providing a space for escapism. Customers, both male and female can be served food and drinks by women dressed as french maids. The cafe itself is designed to feel like a home making the experience all that more personal. The narratives of such spaces exist in the setting of the building and the costumes of the staff (and sometimes the customers). An open-ended space designed to foster imagination and make believe not unlike many of the VR experiences I have tried but particularly similar to Happy Oshare Time.

Conclusion

It would be interesting to compare how Japanese people familiar with associated genres such as anime, cos play, manga and Purikura inhabit this particular VR space. Even with my limited knowledge of these Japanese practices I found myself embodying a persona of a character that has derived from an amalgamation of these earlier practices and genres. Yes that is me dressed up as chocolate with rainbow coloured eyes!

ReferencesChalfen, R.and Murui, M. (2001) Print club photography in Japan: Framing social relationships. Visual Studies, Vol. 16, No. 1, p. 55–73

ReferencesChalfen, R.and Murui, M. (2001) Print club photography in Japan: Framing social relationships. Visual Studies, Vol. 16, No. 1, p. 55–73Geertz, C. (1973) The interpretation of Cultures.

Guth, C. (1996) Japanese Art of the Edo Period. Everyman Art Library.

Kress, G. (2003) Literacy in the New Media Age. London & New York: Routledge.

Miller, L. (2003) Graffiti Photos: Expressive art in Japanese girls; culture. Harvard Asia Quarterly, vol.2, no. 3 summer 2003, p. 31-42.

Okabe, D., Chipchase, J. , Ito, M. & Shimizu, A. (2006) The Social Uses of Purikura: photographing, modding, archiving and sharing. PICS Workshop, Ubicomp 2006: 1-6.

Modes, Materials and Performance in the Design of Location-based VR

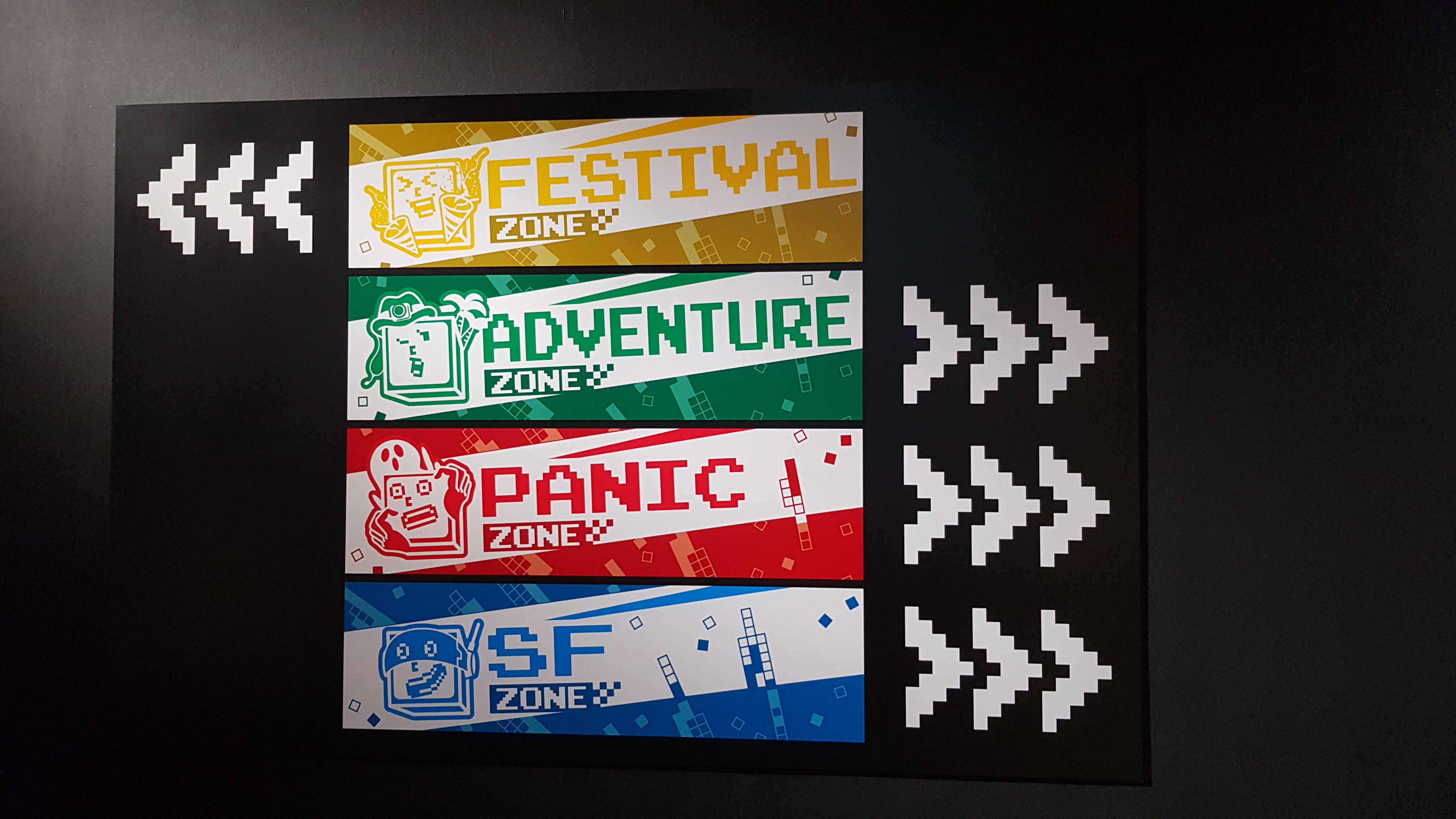

The VR Park Shibuya is an arcade hosting location-based VR experiences. These are site specific content designed for VR play away from the home setting. As a result, location-based VR experiences often have a physical component which provides a different experience to that which can be achieved on a home console such as the Play Station VR. This is something more akin to fit in with the ‘experience economy’ and thus in the best case scenarios the physical set can bring an extra dimension to the VR play worthy of making an audience feel they are paying for an “experience” they could not have elsewhere.

The VR Park occupies one floor of a well established game centre. Each floor is dedicated to different types of gaming content. The ground floor for example has mostly prize based games like the UFO catcher below:

I made notes about each of the experiences I tried in order to understand how they related to different modes of communication and materials to think about what each brought to the various overall experiences. Gunther Kress (2010) states that modal choices are brought together to produce one overall text with each mode playing a distinct role: ‘Each mode does a specific thing: image shows what takes too long to read, and writing names would be difficult to show’ (p. 1). Kress goes on to say that each mode lends itself to ‘doing different kinds of semiotic work; and each has distinct potential for meaning.’ (ibid). Given that the design and production of location-based VR experiences is so new an understanding is needed of how the ways in which modes and materials are used adds or distracts from the overall experience.

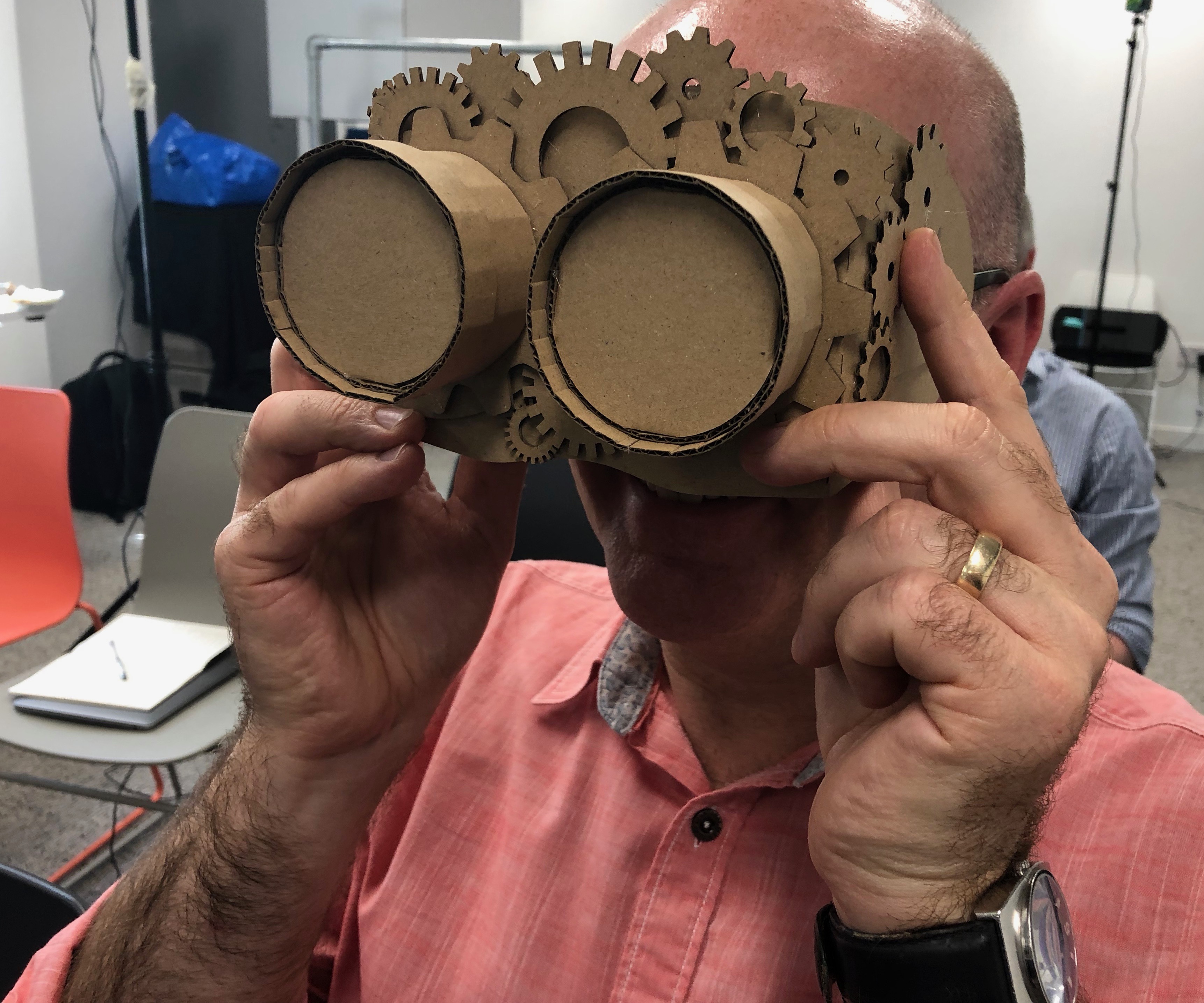

In my teaching on the MA in Information Experience Design at the Royal College of Art this is something I ask students to think about when designing their own work. The following is an example of how MA IED graduate Felix Scholder responded to this with his VR experience about Netsuke:

Truck Coaster

This experience consisted of a physical truck of a roller coaster combined with the VR experience of travelling through rail tracks in a jungle. The experience ended by crashing the audience into a pile of hidden gold treasure

Physical Materials: Roller coaster truck with metal hand rails. Large enough for four players to use the experience at the same time.

On-boarding: Seat belt on, staff state to hold the hand rails throughout the experience. They also helped each player put the headset on.

Visual Aesthetic: Low modality

Sound: Narration of emotions

I ended up playing this game twice and this got me thinking about repeat play. The first time I felt the emotions that had been designed for me to experience but the second time around there were no surprises and as a result I felt less emotional heightened.

Across the course of the field trip, I began to think about how important or not it is for a game to offer a repeatable experience. Talking with our industry partners Hashilus and the Location-based VR Association about this, they mentioned that some games are designed so that the VR element can be updated without the need to engineer a new physical experience. If this is the case how far can a VR experience where the audience needs to sit in a roller coaster truck be pushed? Different types of setting for the rollercoaster? Would that be its limitation?

Angus and I talked about the emotional narration in this experience. A constant narrative about how the experience feels. Angus said he thought this was to compensate for the fact that although you are on the ride other people you cannot share the emotional experience with them as such, because you are largely separated by the HMD and the soundtrack for the experience. I noted that it also seems to follow a pattern of emotional narration that can be found in more wide spread examples of Japanese meaning making practices:

‘Often in Japanese rather than information-sharing, it is the subtextual emotion-sharing that forms the heart of communication’Soloman’s Carpet

(Maynard, 1993, p.4)

This is a two-player experience designed and made by Hashilus.

Materials: Rug with a roped barrier around it. The rug can be felt under foot and thus provides a level of grounding. The rope gives the user something to hold onto and another link to the physical world while in the virtual one.

MU VR

MU VR was a social game in which we started by sitting around a table designed to look like a conference room. We were given a mission that as news reporters we would find ourself on another planet and have the chance to photograph aliens. The reporter to capture the best image would be crowned “top scoop” and have their picture published in a magazine.

Physical Materials: A circular table with chairs around it.

Visual: The table in the Virtual space looked different form the physical one we were sat at. Does this matter?

The game got me thinking about the variety of ways in which players need to be on-boarded into VR experiences While we were waiting to play MU VR I was given the above instructions to read. They made little sense to me ahead of being in the experience. There were also instructions in the game itself and a member of staff stood by to help us play too. When we visited our industry partners Hashilus and the Location-based VR Association we were told how one of the biggest resources for location-based VR experiences is the need to have staff to facilitate use, and they were trying to find means to reduce this cost by exploring ways for all the on-boarding to take place in the experience itself. This can be seen in the example below where the instructions for how to put on the HMD are situated on a screen next to where money is inserted to enable use:

Jungle Bungee VR

In this experience it became clear that there is also an opportunity for the on-boarding to play a role in getting the audience into character for the VR experience too. Before being allowed to take part in the Bungee experience I was asked by staff to sign a waiver form in the event of accident or death. Our group were left unsure as to whether this was an actual waiver or just to put you in the mood for the experience and heighten some tension a head of the jump in the same way a bungee jump in the physical world might do.

Overall the experiences I tried at the VR park gave me a chance to begin reflecting on the role of modes, materials and performance in designing a location-based VR experience.

References

Kress, G. (2010) Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Oxon: Routledge.

Maynard, S. (1993) Discourse Modality: Subjectivity, Emotion and Voice in the Japanese Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Related Publications

Yamada-Rice, D., Dare, E. Main, A., Potter, J., Ando, A. Miyoshi, K., Narumi, T., Beshani, S., Clark, A., Duszenko, I. Love, S., Nash, R., Rodrigues, D., Stearman, N. (2020)Location-Based Virtual Reality Experiences for Children: Japan-UK Knowledge Exchange Network: Final Project Report. Available online here

Images: Exploring Location-based VR in Japan

Related Talks

Dare & Yamada-Rice (2021) Virtual [UN]Reality: the role of magic in immersive storytelling, Immersive Storytelling Symposium, Lakeside Arts, 2nd Nov 2021

Invited Speaker: Yamada-Rice, D. (2021) Children and Virtual Reality, UCL Centre for Multimodality Talks, 15th October, 2021

Invited Panellist: Yamada-Rice, D. (2020) VR & Children: Opportunities and Critiques, Interaction Design and Children (IDC), Virtual Conference, 24th June 2020

Invited Keynote: Yamada-Rice, D. (2020) Children & VR: Game + Design Education, PUDCAD Universal Design Education Practice Conference, 24 June 2020, virtual conference

Invited Keynote: Yamada-Rice, D. (2019) Clash of Realities, Cologne, Germany, 20th Nov 2019

Image: Project Team

Image: Project Team